Language family maps

Last week, I assigned Bernhard Comrie's (2017) chapter 'The Languages of the World' (from The Handbook of Linguistics, 2017) to a class. It's a basic overview of the world's language families, which is what I wanted them to read, but for one thing: there are no maps in it. I overcompensated in class by presenting a 30-item list of maps, because some things are just so much easier to understand using visual representations. I decided to post some of the best ones I could find here, for future reference and in order to invite you to post better ones in the comments.

This blog has featured posts on maps before, by Hedvig on how to best represent linguistic diversity on maps and by Matt on new approaches to ethnographies-linguistic maps. It's clear that the kind of maps that are typically used to depict the spatial distribution of languages of a single language family are fraught with difficulties. Typically they deal with multilingualism very poorly, the data they display is usually from different sources that could be decades if not centuries apart, some maps below are based on ethnography and not on linguistics and how these line up is often not straightforward, the list goes on and on.

That being said, classification in terms of family membership is one of the primary means of classifying languages, and only through the history of language families we can understand how some languages have spread and others have died. Hence, the geographical perspective on language families is an important one. Here I am mostly after polygon maps of language families, and not maps per country (big on Ethnologue) or using points (to be found on Glottolog and LL-MAP).

During my search, I found that many handbooks do not feature maps (just one example, The Tai-Kadai Languages by Diller, Edmondson and Luo), which I found odd as it seems such an obvious thing to include. There is a lot of stuff to be find on the web, though. There are maps on the Encyclopaedia Britannica, unfortunately behind a paywall but many can be found online in a reasonable format, one is featured below on the Khoisan families, for instance. Muturzikin has polygon maps on continents and countries, so not specific to families, but of course in certain cases this doesn't really matter (like Australia). Then there are some blogs with collections of maps, such as Native Web and this older website. There is also this collection of resources, compiled by Candace Luebbering.

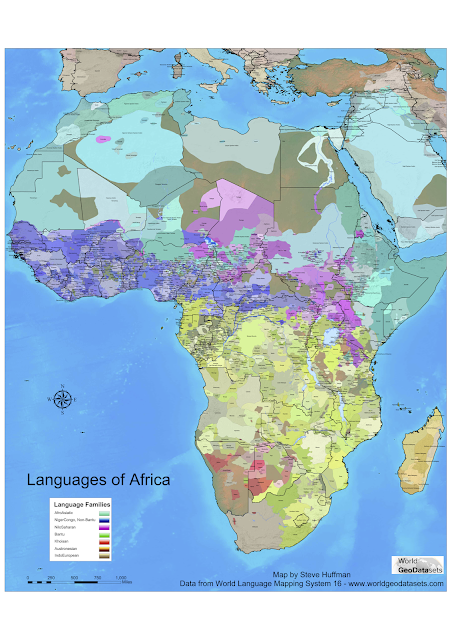

Let's start with a journey around the world in language family maps, starting with Steve Huffmann's map of Africa:

And to the north, smaller families that were once subsumed under the family name 'Nilo-Saharan' (marked in shades of pink in Huffman's map), but which are now considered to be smaller, separate families:

Furthest to the north and also evident in the Middle East is Afroasiatic (marked in shades of light blue on Huffmann's map):

With these languages of Northern Africa, we arrive in Eurasia. One of the most wide-spread families of Eurasia is Indo-European. In the map below, the eastern part of Eurasia including India is not very well depicted at all, unfortunately.

The Caucasus Mountains and surrounding valleys are home to the Caucasian language families:

Even wider across the Eurasian continent than Indo-European stretches the Altaic language family, containing the Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic families.

Altaic has long been contested, but is now included in proposals on a language family termed Transeurasian, which includes Altaic as well as Korean and Japonic:

In northern Eurasia, we find Uralic, which includes several big European languages, such as Finnish, Hungarian, and Estonian:

At the very eastern end of the Eurasian continent, there is located the small family of Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages:

The second is a really nice map from Sagart et al. (2019), a recent study on the age of origin and the homeland of Sino-Tibetan:

I hope you enjoyed this trip around the world, limited though these maps may be. Please post better maps in the comments. If this post is a success, I will devote my next blog to isolates, languages with no known relatives. Enjoy!

References

Bellwood, Peter. (2013). First migrants: Ancient migration in global perspective. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Gray, RD, A J Drummond, and S J Greenhill. 2009. “Language Phylogenies Reveal Expansion Pulses and Pauses in Pacific Settlement.” Science 323 (5913): 479–483. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1166858.

Fortescue, Michael (2011). "The relationship of Nivkh to Chukotko-Kamchatkan revisited". Lingua. 121 (8): 1359–1376. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2011.03.001.

Kolipakam, Vishnupriya, Fiona M. Jordan, Michael Dunn, Simon J. Greenhill, Remco Bouckaert, Russell D. Gray, and Annemarie Verkerk. 2018. “A Bayesian Phylogenetic Study of the Dravidian Language Family.” Royal Society Open Science 5: 171504.

Krauss, Michael E. (1988). Many Tongues - Ancient Tales, in William W. Fitzhugh and Aron Crowell (eds.) Crossroads of Continents: Cultures of Siberia and Alaska (pp. 144-150 ). Smithsonian Institution.

Loukotka, Čestmír. (1968). Johannes Wilbert, ed. Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: Latin American Center, University of California.

Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Robbeets, Martine, and Remco Bouckaert. (2018). “Bayesian Phylolinguistics Reveals the Internal Structure of the Transeurasian Family.” Journal of Language Evolution 3 (2): 145–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/jole/lzy007.

Sagart, Laurent, Guillaume Jacques, Yunfan Lai, Robin J. Ryder, Valentin Thouzeau, Simon J. Greenhill, and Johann-Mattis List. 2019. “Dated Language Phylogenies Shed Light on the Ancestry of Sino-Tibetan.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1817972116/

Sidwell, Paul. (2009). Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: History and state of the art. München: LINCOM.

This blog has featured posts on maps before, by Hedvig on how to best represent linguistic diversity on maps and by Matt on new approaches to ethnographies-linguistic maps. It's clear that the kind of maps that are typically used to depict the spatial distribution of languages of a single language family are fraught with difficulties. Typically they deal with multilingualism very poorly, the data they display is usually from different sources that could be decades if not centuries apart, some maps below are based on ethnography and not on linguistics and how these line up is often not straightforward, the list goes on and on.

That being said, classification in terms of family membership is one of the primary means of classifying languages, and only through the history of language families we can understand how some languages have spread and others have died. Hence, the geographical perspective on language families is an important one. Here I am mostly after polygon maps of language families, and not maps per country (big on Ethnologue) or using points (to be found on Glottolog and LL-MAP).

During my search, I found that many handbooks do not feature maps (just one example, The Tai-Kadai Languages by Diller, Edmondson and Luo), which I found odd as it seems such an obvious thing to include. There is a lot of stuff to be find on the web, though. There are maps on the Encyclopaedia Britannica, unfortunately behind a paywall but many can be found online in a reasonable format, one is featured below on the Khoisan families, for instance. Muturzikin has polygon maps on continents and countries, so not specific to families, but of course in certain cases this doesn't really matter (like Australia). Then there are some blogs with collections of maps, such as Native Web and this older website. There is also this collection of resources, compiled by Candace Luebbering.

Let's start with a journey around the world in language family maps, starting with Steve Huffmann's map of Africa:

Steve Huffmann's map of African languages using WLMS 16

Africa is home to the biggest language family of the world (in number of languages, at least currently): Atlantic-Congo, in Huffmann's map marked in shades of purple (non-Bantu branches) and green (Bantu). To the south of the Atlantic-Congo languages, we find the Khoisan languages (marked in shades of red on Huffmann's map):

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Khoisan language families

And to the north, smaller families that were once subsumed under the family name 'Nilo-Saharan' (marked in shades of pink in Huffman's map), but which are now considered to be smaller, separate families:

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Nilo-Saharan language families

Furthest to the north and also evident in the Middle East is Afroasiatic (marked in shades of light blue on Huffmann's map):

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Afroasiatic language family

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Indo-European language family

Map of Caucasian peoples, source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Caucasus-ethnic_en.svg

Even wider across the Eurasian continent than Indo-European stretches the Altaic language family, containing the Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic families.

Map on prior distribution of Altaic languages, from Bellwood (2013: 164)

Altaic has long been contested, but is now included in proposals on a language family termed Transeurasian, which includes Altaic as well as Korean and Japonic:

The distribution of the Transeurasian languages (Robbeets and Bouckaert 2018: 146)

In northern Eurasia, we find Uralic, which includes several big European languages, such as Finnish, Hungarian, and Estonian:

source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Linguistic_map_of_the_Uralic_languages_(en).png

At the very eastern end of the Eurasian continent, there is located the small family of Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages:

Map of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages and their neighbours, Fortesque (2011)

Here is a second, more colourful map showing the neighbours of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan family across the Bering Strait:

Map of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages and their neighbours, Krauss (1988)

Then we start slowly moving from Eurasia to South, East, and Southeast Asia. The Dravidian language family is located in the south-east of the Indian subcontinent, as well as in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nepal:

Map of the Dravidian languages, Kolipakam et al. (2018)

To the north but very close to the Dravidian languages are the Munda languages, one of the subfamilies of Austroasiatic, which spreads all the way from the eastern Indian subcontinent to Malaysia:

Map of the Austro-Asiatic languages by Pinnow (1959), as cited by Sidwell (2009)

The Austroasiatic languages (also known as Mon-Khmer) are intermingled with a whole range of other families, including Indo-European and Dravidian in India, and Tai-Kadai, Hmong-Mien, and Sino-Tibetan in Southeast Asia. Sidwell (2009: 3-4) comments on how little is known regarding the internal relationships of the Austroasiatic, which must be so interesting given their dispersal and interaction with languages from other families. The following is a map of the Hmong-Mien language family from The Language Gulper:

Map of the Hmong-Mien language family from The Language Gulper

The following are two maps of the Tai-Kadai family, one from Encyclopaedia Britannica and one from Wikipedia:

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Tai-Kadai language family

source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taikadai-en.svg

This leaves us with the last huge family of the Eurasian continent, Sino-Tibetan. The first map is another map from The Language Gulper:

Map of the Sino-Tibetan language family from The Language Gulper

The second is a really nice map from Sagart et al. (2019), a recent study on the age of origin and the homeland of Sino-Tibetan:

Map of the Sino-Tibetan language family from Sagart et al. (2019)

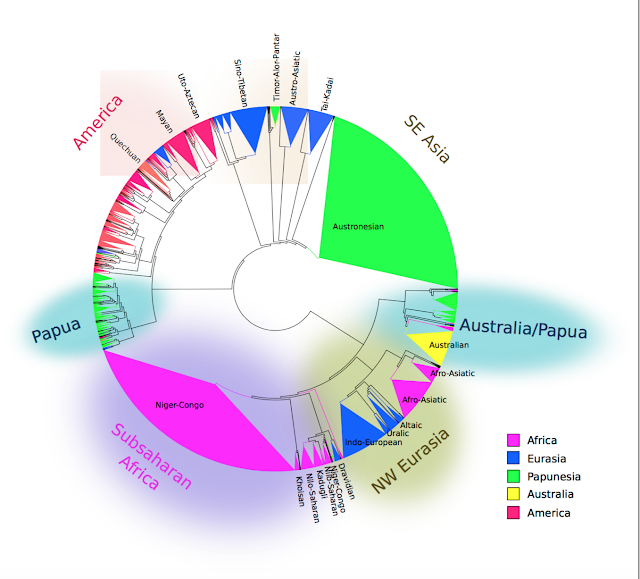

For Austronesian, the second-largest language family of the world, there are various maps below. The first is from Bellwood (2013), displaying migration patterns. The second is a points map giving internal classifications on the basis of the phylogenetic analyses by Gray et al. (2009). The third I got from Hedvig and is a map of Oceania including Australia:

Map of population movements part of the Austronesian expansion from Bellwood (2013: 192)

Map on the Austronesian expansion from Gray et al. (2009)

Languages in Oceania by language family, courtesy of Hedvig Skirgård

As can already be seen in the map just above - the island of New Guinea is incredibly diverse, home to many Austronesian languages but also to the many Papuan language families. Muturzikin has a great map of these which is too big for me to copy here; what does fit is this map of the biggest of the Papuan language families, Trans-New-Guinea:

Map of the Trans-New-Guinea language family by Muturzikin

The same goes for Muturzikin's map of Australia, it's too big to copy here. Below is the beautiful map compiled by David Horton:

AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia, compiled by David Horton

Muturzikin's map of Australia is a contemporary map, in other words it shows a patchy distribution of indigenous languages, surrounded by English. The same is true for some maps of the Americas. The following is a map of North America:

Map based on two maps by cartographer Roberta Bloom appearing in Mithun (1999:xviii–xxi), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Langs_N.Amer.png

And the next two are two maps of Meso-America, the first displaying the linguistic situation at the time when Europeans first arrived in the area, the second (more or less) contemporary:

Map of Meso-American indigenous languages, source unknown

Map of Meso-American indigenous languages from The Language Gulper

The same applies to these next maps of South-America. The first map (kindly brought to my attention by Olga Krasnoukhova) presents the situation at some point in the past, the second presents a more contemporary view, showing the rate at which minority languages are dwindling and dying out.

Ethnolinguistic map of South America by Loukotka (1968)

Map of South American indigenous languages from The Language Gulper

I hope you enjoyed this trip around the world, limited though these maps may be. Please post better maps in the comments. If this post is a success, I will devote my next blog to isolates, languages with no known relatives. Enjoy!

References

Bellwood, Peter. (2013). First migrants: Ancient migration in global perspective. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Gray, RD, A J Drummond, and S J Greenhill. 2009. “Language Phylogenies Reveal Expansion Pulses and Pauses in Pacific Settlement.” Science 323 (5913): 479–483. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1166858.

Fortescue, Michael (2011). "The relationship of Nivkh to Chukotko-Kamchatkan revisited". Lingua. 121 (8): 1359–1376. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2011.03.001.

Kolipakam, Vishnupriya, Fiona M. Jordan, Michael Dunn, Simon J. Greenhill, Remco Bouckaert, Russell D. Gray, and Annemarie Verkerk. 2018. “A Bayesian Phylogenetic Study of the Dravidian Language Family.” Royal Society Open Science 5: 171504.

Krauss, Michael E. (1988). Many Tongues - Ancient Tales, in William W. Fitzhugh and Aron Crowell (eds.) Crossroads of Continents: Cultures of Siberia and Alaska (pp. 144-150 ). Smithsonian Institution.

Loukotka, Čestmír. (1968). Johannes Wilbert, ed. Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: Latin American Center, University of California.

Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Robbeets, Martine, and Remco Bouckaert. (2018). “Bayesian Phylolinguistics Reveals the Internal Structure of the Transeurasian Family.” Journal of Language Evolution 3 (2): 145–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/jole/lzy007.

Sagart, Laurent, Guillaume Jacques, Yunfan Lai, Robin J. Ryder, Valentin Thouzeau, Simon J. Greenhill, and Johann-Mattis List. 2019. “Dated Language Phylogenies Shed Light on the Ancestry of Sino-Tibetan.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1817972116/

Sidwell, Paul. (2009). Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: History and state of the art. München: LINCOM.

Comments

Post a Comment