Some language universals are historical accidents

There are surprisingly few properties that all languages share. Pretty much every attempt at articulating a genuine language universal tends to have at least one exception, as documented in Evans and Levinson's article 'The Myth of Language Universals'. However, there are non-trivial properties that are found in if not literally all languages, enough of them and across multiple language families and independent areas of the world, that they demand an explanation.

An example is the fact that languages have predictable word orders. Languages differ in whether they allow the verb to come before or after the object (English has it before, Japanese after). They also differ in whether they have pre-positions (such as English ‘on the table’) or post-positions (such as Japanese テーブルの上に teburu no ue ni ‘’the table on’). If a language has the verb before the object then it tends to have prepositions rather than postpositions, as in English; if the verb is after the object, it is a good bet that the language will have postpositions rather than prepositions (these rules hold for 926/981 languages in WALS, not controlling for relatedness). The ordering of different elements in a sentence such as the noun and adjective, noun and possessive, and so on, are to some extent free to vary among languages, but again tend to fall into correlating types.

Why should knowing the word order of one category in a language help predict the orderings of other categories? Many people have taken facts such as this as evidence that language is shaped by principles of harmony across grammatical categories, or evidence of Universal Grammar. Another possible explanation is that languages which have similar word orders for different grammatical categories are somehow easier to learn, or easier to use.

However, I would argue that at least some of these patterns are not evidence of our psychological preferences, but are accidental consequences of language history. This post is a response to a couple of blog posts written by Martin Haspelmath this week on Diversity Linguistics Comment (here, and here with Sonia Cristofaro), which argued that historical explanations of universals still need to invoke constraints on language change, and that 'the changes are often adaptive, and that in such cases a precise understanding of the diachronic mechanisms is not necessary (though of course still desirable).' I disagree, in the particular case of word order correlations, and I will argue specifically in this post that word order correlations are a consequence of grammaticalization. In arguing this I'm building on work by Aristar (1991) and Givon (1976), but developing the argument to refute Haspelmath's points. I will present the background of the argument first and then discuss his points in more detail.

Grammaticalization is the process by which new grammatical categories can be formed from other (often lexical) categories. For example, Mandarin Chinese has a class of words which might be called prepositions if they were in a European language, but which really have their historical roots in verbs. An example is 從 cóng which in modern Mandarin is a preposition meaning ‘from’ but which in Classical Chinese was a verb meaning ‘to follow’, as these two sentences illustrate.

我 從 倫敦 來

I from London come

‘I come from London’

天下 之 民 從 之

under-heaven POSSESSIVE people follow him

‘Everyone in the world follows him’ (孟子萬章上 Mengzi Wanzhang Shang: from the 古代漢語辭典 Gudai Hanyu Cidian)

The word 從 cóng has changed its meaning from ‘follow’ to a more abstract spatial meaning ‘from’. It has also lost its ability to be used as a full verb, requiring another verb such as ‘come’ in the sentence, just as English requires a verb in the sentence ‘I come from London’ (*’I from London’ and its equivalent *我從倫敦 are ungrammatical). Other Chinese prepositions such as 跟 gēn ‘with’, also have a verbal origin, while many preposition-like words such as 給 gěi 'for' and 在 zài 'in/at' retain verbal meanings ('give' and 'to be present') and verbal syntax (such as being able to be used as the sole verb in the sentence and to take aspect marking).

Why is this relevant to word order universals? Because if so-called prepositions in Chinese were once historically verbs which have since lost their verbal uses, this can explain why the two grammatical classes have the same word ordering: they were once the same category, and they simply haven’t changed their word orders since then. Since the verb precedes the object in Chinese, as in the Classical Chinese sentence given above (從之 cóng zhī ‘follow him’), the preposition in modern Chinese also precedes the object (從倫敦 cóng Lúndūn ‘from London’).

It is incorrect to say that Chinese has prepositions and verb-object order because this is a combination that is easy to process or learn, or because the categories are in some other sense ‘harmonious’. The real explanation is that verbs and prepositions in Chinese have a common ancestor, and have simply preserved their word orders since then. This is a subtle variant of Galton’s problem, by which the historical non-independence of data points can create correlations that are not causal. Most examples of this are from relatedness of whole languages or cultures, for example the spurious correlation between chocolate consumption and Nobel Prize winners; or the way that a maths teacher at my school was exercised by the fact that in many languages ‘eight’ and ‘night’ often rhyme or are similar (e.g. German acht and nacht, French huit and nuit, Italian otto and notte) - there's nothing mystical here, the explanation here being that the words in these languages descend from common Proto-Indo-European roots *okto and *nekwt, which happen to be similar.

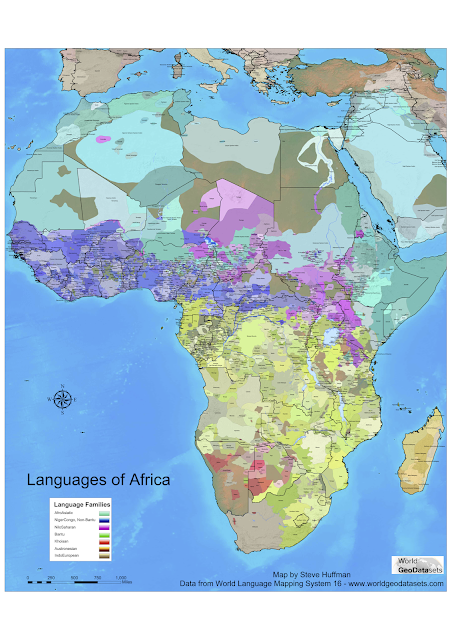

Just as languages and cultures can be related, individual words in a language can be related, such as prepositions and verbs, and hence share properties such as their word order. It turns out that the process of grammatical categories developing from other categories is extremely common and attested in every language family and part of the world (e.g. Heine and Kuteva 2008). Verbs can change into adpositions as in the Chinese example above (also found in languages such as Thai and Japanese), while nouns also often change into adpositions (as in many Niger-Congo languages such as Dagaare, where adpositions are all also body parts such as zu 'on/head'). Other word order correlations can be explained in a similar way, such as the relationship between adjective-noun and genitive-noun order, and even verb-object order and genitive-noun order (because of grammaticalizations such as me-le e kpe dzi 'I am on his seeing' as a way of expressing 'I am seeing him' in Ewe, Claudi 1994). I give further examples in different languages in a short article I wrote for Evolang (2012), in which I make the point that these processes should be considered a serious confound to an explanation which tries to claim that there is a causal link between word orders across grammatical categories.

But can't both explanations be correct? This is the response I hear from every linguist that I've described this argument to, including Balthasar Bickel, Morten Christiansen, Simon Kirby and now also Martin Haspelmath in his blog post when he says '...while everyone agrees that common paths of change (or common sources) have an important role to play in our understanding of language structure, I would argue that the changes are often result-oriented, and that in such cases a precise understanding of the diachronic mechanisms is not necessary (though of course still desirable).' In short, does grammaticalization happen in order to create correlated word orders?

No. Objections like that are missing the point about non-independence. Grammaticalization happens, causing two grammatical constructions to exist where there was previously one. These two constructions are likely to have the same word order, on the reasonable assumption that constructions are more likely than not to keep the same word order over time (an assumption also vindicated by work by Dunn et al. described below). You have to control for this common ancestry if you wish to claim that the correlation in word orders across constructions is causal. It is as if people wanted to claim that there was a deeper ecological reason why chimpanzees and humans share 98.8% of their DNA, rather than just the primary historical reason which is that they have a common ancestor.

There are interesting ways that both explanations could be true, if this non-independence of constructions is successfully controlled for, but evidence for this is surprisingly elusive. One possibility is that only some kinds of grammaticalization happen, namely the types which produce word orders that are easy to process. Haspelmath makes this suggestion in his post: 'I certainly think that studying the diachronic mechanisms is interesting, and I also agree that the kind of source of a change may determine parts of the outcome, but to the extent that the outcomes are universal tendencies, I would simply deny the relevance of fully understanding the mechanisms. In many of the cases that Cristofaro discusses, I feel that the “pull force” of the preferred outcome may well have played a role in the change, though I do not see how I could show this, or how one could show that it did not play a role.'

I agree that this might be possible ("the “pull force” of the preferred outcome may well have played a role in the change"), but there is currently no evidence for this. The main way to test it would be to compile a database of grammaticalizations across languages and to see whether certain grammaticalizations happen only in certain languages: for example, do postpositions only develop from nouns in a genitive construction (the table's head -> the table on) if the language also places the verb after the object? It is easy to find exceptions to that such as Dagaare, which has verb-object order but has postpositions because those postpositions develop from nouns, and it has genitive-noun order. In a large database, there may be all sorts of interesting constraints on what grammaticalizations can occur, as well as geographical patterns, and it may of course turn out that word order is one constraining factor, but currently this hypothesis is unsubstantiated.

Another way that word orders might be shown to be causally related to each other is if a change in one word order can be shown to be correlated with a change in another word order in the history of a language, or in its descendants. For example, if a language has verb-object order and prepositions but then changes to having object-verb order and postpositions, then this suggests that the two word orders are functionally linked (if this event takes place after any grammaticalization linking these verbs and postpositions). The only solid statistical test of this so far has been an article by Dunn, Greenhill, Levinson and Gray in Nature (2011). They tested the way that four language families have developed (Bantu, Austronesian, Indo-European and Uto-Aztecan) and tested models of word order change using a Bayesian phylogenetic method for analysing correlated evolution. What they found was that some word orders do indeed change together. For example, the order of verb and object seems to change simultaneously with the order of adposition and noun in Indo-European, as shown in the tree reproduced from their paper below (red square = prepositions, blue square = postpositions, red circle = verb-object, blue circle = object-verb, black = both):

Is this convincing evidence that there is a functional relationship between the two word orders after all, after factoring out grammaticalization? It would be, except that language contact is not controlled for in this case. What could be happening is that some Indo-European languages in India have different word orders because of the languages that they are near, such as Dravidian languages, which also have object-verb order and postpositions. A similar point could be made about the Austronesian languages that undergo word order change, which are found in a single group of Western Oceanic languages on the coast of New Guinea, which is otherwise dominated by languages with object-verb order and postpositions.

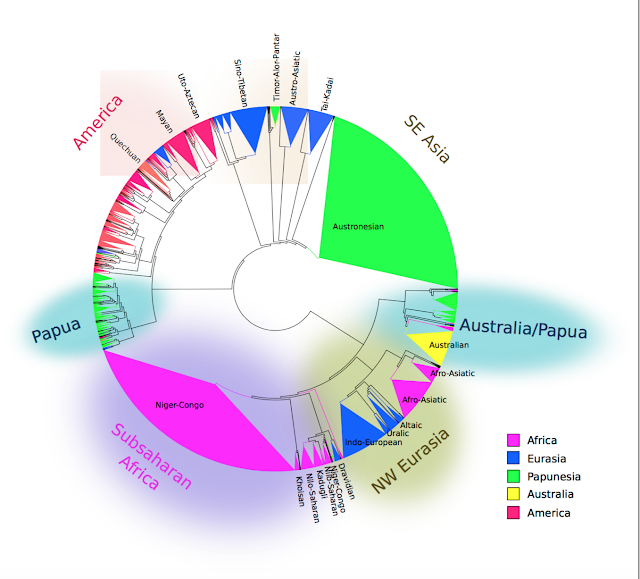

An interesting result of their paper is that word orders are very stable, staying the same over tens of thousands of years of evolutionary time (i.e. summing the time over multiple branches of the families), supporting the assumption that I described above that word orders tend to be stay the same. The main result of this test has been that language families differ in which word order dependencies they show, and many of them are likely to reflect events of word order change due to language contact, but the test has also been acknowledged by Russell Gray and others as having low statistical power, and hence not conclusive evidence either for or against there being genuine functional links between word orders. A promising approach in the future is to apply the same phylogenetic test to the entire world, attempting to use it on a global phylogeny - a world tree of languages that does not have to be completely accurate, but simply has to incorporate known information about language relatedness, and perhaps some geographically plausible macro-families to control for linguistic areas where languages have shared grammatical properties across families (such as Southeast Asia or Africa).

Another intriguing line of inquiry is to work out what particular predictions a theory of processing or learnability would make about word order patterns across languages, and whether these predictions are in fact different from an explanation that invokes grammaticalization. Hawkins (2004) is an example, which shows that there are word order patterns such as 'If a prepositional language preposes genitives, then it also preposes adjectives', and argues that these are predicted on the basis of the relative length of constituents such as possessive phrases and adjectives. These particular rules worked in Hawkins's sample of 61 languages, but fail on larger databases such as WALS (38 out of 50 languages contradict the rule just given, for example).

Whether or not these attempts to demonstrate the role of processing are successful, a large part of the story of why word universals exist is the evolution of grammar. When we try to explain why adpositions correlate in their ordering with other categories, we should remember to ask why languages have a separate grammatical category of adpositions at all. Why does grammaticalization happen, forming a distinct class of adpositions, rather than languages just expressing spatial relations with nouns and verbs? Why are English prepositions such as for, to, on and so on etymologically obscure, whereas in some languages such as Dagaare and Chinese many adpositions are homophonous with verbs and nouns, to the point that is doubtful that these 'adpositions' really constitute a separate class (as opposed to a sub-class of verbs, and relational nouns)? One possibility is that we store individual constructions rather than words, and these constructions once individually stored can end up being transmitted as independent units between speakers. To take a hypothetical example, in a language which uses body-part terms to convey spatial meanings such as saying table's head to mean 'on the table', the particular use of head as a spatial word may be stored separately from the body-part use of 'head'. Once that happens, it is possible for the body-part sense of head to be lost in a community of speakers and just the spatial sense retained (for example, the English front derives from the Latin frons 'forehead').

This process often creates a chain of intermediate cases between nouns and adpositions, such as in Tibetan, where some adpositions require genitive marking such as mdun 'front' ('the house's front'), while others used genitive marking in the Classical language but no longer allow it (nang 'inside') (DeLancey 1996:58-59). There are similarly ambiguous cases in English where words such as regarding can be both a verb form and a preposition. It is worth asking whether any language has ever developed adpositions any other way: it is hard to imagine a language inventing adpositions from scratch (Edward de Bono managed to get the phrase 'lateral thinking' to catch on among English speakers, but not his invented preposition po), and they instead catch on better if they are extended uses of already existing words, such as English regarding. It is likely that most words began as extensions of other words, more generally, rather than invented out of nothing, perhaps with some exceptions such as 'Quidditch', or ideophones. It is possible that some languages may actually invent adpositions, such as sign languages (which can use iconic signs for 'up' and 'down' for example), but if the hypothesis is correct that this is not normally what happens in spoken languages, then the historical default ought to be that adpositions share the same syntactic properties, including their word order, as other categories. The real thing to explain is not why they correlate in their word orders with other categories, but why it is ever the case that they do not correlate.

As an analogy, some languages have unusual non-correlations of word orders across constructions, such as German which has verb-object order in main clauses and object-verb order in subordinate clauses, or Egyptian Arabic* in which numerals precede the noun except for the number 'one' and 'two', which follow it. It is true that most languages in the world have a 'correlation' between the ordering of the number 'one' and the ordering of other numerals, to the point of making this another word order universal: but a functional explanation for this fact ('A language is easier to learn if the word order is the same for all numerals') would be banal, and would miss the fact that the historical default in most languages has been for the orderings to be correlated, simply because 'one' is normally treated as a member of the same grammatical class as other numerals. I'm arguing that the correlation between adpositions and verb-object ordering is also likely to be a historical default due to grammaticalization, rather than a situation which languages converge on for reasons of processing or learnability.

I see word order correlations, in short, mostly as an unintended consequence of the way that grammatical categories evolved in most languages, not as an adaptive solution to processing or language acquisition. Martin Haspelmath seems to disagree with the spirit of this type of historical argument in his blog post, however, which states (to repeat): 'Quite a few people have argued in recent times that typological distributions should be explained with reference to diachronic change...but I would argue that the changes are often adaptive and result-oriented, and that in such cases a precise understanding of the diachronic mechanisms is not necessary (though of course still desirable).' My main point in this post is that I disagree with both parts - that an understanding of the history of languages is unnecessary to understand word order correlations (it is in fact the main story behind them), and that these changes are adaptive and result-oriented (there is little evidence so far that these grammaticalizations are geared towards producing harmonic word orders).

He has some more specific objections to historical arguments, reproduced below:

"(A) Recurrent paths of change cannot explain universal tendencies; universal tendencies can only be explained by constraints on possible changes (mutational constraints).

(B) Diverse convergent changes cannot be explained without reference to preferred results.

(C) If observed universal tendencies are plausible adaptations to language users’ needs, there is no need to justify the functional explanation in diachronic terms."

Objection (A) I disagree slightly with, because common pathways of change are enough to be a serious confound to functional explanations of language universals, as I have tried to argue. How common is 'common'? In an ideal world, common enough that, for example, the number of languages predicted to have word order correlations is about 926/981, simply using a statistical model that assumes grammaticalization, inheritance of word order in language families, and language contact. I have only listed some examples in this post, but their existence in multiple families and parts of the world, coupled with the stability of word orders in families, is enough to make the relatedness of constructions an important confound. I acknowledge that an actual quantitative test is needed of whether they are common enough to explain the entire distribution of word orders, which would rely on a database of grammaticalizations - if there is enough data on grammaticalization to ever be able to test this.

Haspelmath is sceptical of 'common pathways of change', viewing these as unfalsifiable, and asks instead for stronger constraints: 'In syntax, one might explain adposition-noun order correlations on the basis of the source constraint that adpositions only ever arise from possessed nouns in adpossessive constructions, or from verbs in transitive constructions, Aristar 1991).' In this post, I suggested a strong constraint, namely that new words normally develop from already existing words and are rarely invented from scratch. Adpositions are therefore likely to develop from words that include, but are probably not limited to, nouns and verbs. The question of what particular grammaticalizations can occur and why some are especially common is of course an interesting subject, but secondary to the main argument of this post, namely that the very existence of these processes is a serious confound to functional explanations of universals.

Point (B) effectively asks why languages converge on patterns such as word order correlations when they take different historical paths, such as Chinese grammaticalizing verbs to prepositions, while Thai grammaticalized (in some cases) possessive nouns. Isn't it a coincidence when both processes conspire on the same result, both verb-object languages having prepositions? Well, in these cases the expected outcome of grammaticalization in both cases was prepositions simply based on the ordering of their source constructions (verb-object, and noun-genitive), so there isn't anything to explain. There are also plenty of counter-examples, such as Dagaare mentioned earlier, which takes the same path as Thai and ends up with non-correlating word orders (verb-object order but having postpositions), because the postpositions come from possessed nouns with a genitive-noun ordering. Again, a database of grammaticalization would tell us how common these exceptions are; if they turn out to be rarer than expected - for example, if there really is a tendency for verb-object languages not to evolve postpositions even when they have the genitive-noun order - then Haspelmath's point (B) may be vindicated. Finally, point (C) is the main one that I disagree with, as I stated above (the history of these categories is all-important, and grammaticalization does not seem to happen with the goal of creating word order correlations). I should add that I am only talking about word order, and may agree with Haspelmath's points in explaining other common linguistic patterns. I am also not denying the relevance of processing to understanding why some word order combinations may be favoured over others, which can be illustrated with sentences such as 'The woman sitting next to Steven Pinker's pants are just like mine' (Pinker 1994) (illustrating the problem of a language having genitive-noun order and noun-relative clause order).

Why am I writing about a relatively minor set of disagreements on a niche question? For me, this subject is interesting because it is about a subtle variant of Galton's problem and the possibility of erroneously inferring causation from correlation, but also because it encompasses three of the greatest discoveries of modern linguistics. One of them is the discovery of word order universals themselves, the unexpected set of rules which allow one to make predictions about word orders in every part of the world from the Europe to the Amazon and New Guinea, with deep implications for the way that grammatical rules are represented in the mind. Word order universals were first elucidated by Joseph Greenberg (1963) and substantiated for over 600 languages (now over 1500) by Matthew Dryer (1992). I sometimes wonder why this discovery was not reported in Nature at the time, given that Dunn et al.'s later article on attempting to refute word order universals was published there. It is an intriguing linguistic fact that has been written about in popular accounts of language such as Pinker's The Language Instinct but which has not yet received a fully satisfactory explanation and awaits further statistical tests, such as a large-scale phylogenetic analysis. Such tests require knowledge of how languages are related to each other, touching on the second 'great discovery' that I would suggest that linguists have made, the way that we can study the history of large, ancient families such as Indo-European and Austronesian (and perhaps soon even larger macro-families).

The third great discovery, though less well-known, is grammaticalization, 'the best-kept secret of modern linguistics' (Tomasello 2005). Languages are systems of complex grammatical categories and sometimes perverse syntactic rules. How did all that get here? Who 'invented' Latin verb endings, or English prepositions? The most satisfying answer that we have is that grammatical words and morphemes tend to develop from already existing elements, and develop their grammatical meanings gradually. The English morpheme -ing for example is claimed to have begun as an ending denoting nouns to do with people such as cyning 'king' and Iduming 'Edomite', and was then extended to be used on verbs as a nominalizer (playing tennis is fun) and then as a marker of continuous aspect (I am playing tennis) (Deutscher 2008). The change from nominalizers to verb endings is mirrored across several language families (see here), and the origin of nominalizers in some languages can be traced back further to noun endings or even full nouns (such as 化 huà 'change' in Mandarin being used a nominalizer in 現代化 xiàndàihuà 'modernization', or sa in Tibetan coming from a noun meaning 'ground, place'). This shows in principle how complex grammar does not need to be invented, but can develop by gradual changes from simple elements such as concrete nouns.

In some cases these links are directly attested in languages with a long written record, such as Chinese. In other cases they are inferred from polysemies or by comparison with related languages. These links differ in how plausible or substantiated they are, and this work therefore needs some attempt at quantification, for example in objectively assessing similarity between forms, or counting instances of known semantic shifts across languages. Above all, attested grammaticalizations need to be gathered into a database in order to test relationships with other properties such as word order. Heine and Kuteva's The Genesis of Grammar (2008) and a well-written popular account The Unfolding of Language (Deutscher 2005) are overviews of grammaticalizations that have been documented across languages, including from nouns to adjectives, case markers, adpositions, adverbs, and complementisers; from verbs to aspect markers, case markers, adpositions, complementisers, demonstratives, and negative markers; from demonstratives to definite articles, relative clause markers, and pronouns; and from pronouns to agreement and voice markers.

These pathways of change by which new categories can be created are the fullest account of the evolution of language that we currently have, a fraction of which are summarised in a tree below from Heine and Kuteva (2008:111). They help us make sense of the inherent fuzziness of closely related categories, and also the formal similarities between them, including correlations in their word orders. Word order universals may turn out to have been shaped in part by other factors such as processing and learnability, but they also tell the story of a linguistic equivalent of the Tree of Life, the history of grammatical categories.

In some cases these links are directly attested in languages with a long written record, such as Chinese. In other cases they are inferred from polysemies or by comparison with related languages. These links differ in how plausible or substantiated they are, and this work therefore needs some attempt at quantification, for example in objectively assessing similarity between forms, or counting instances of known semantic shifts across languages. Above all, attested grammaticalizations need to be gathered into a database in order to test relationships with other properties such as word order. Heine and Kuteva's The Genesis of Grammar (2008) and a well-written popular account The Unfolding of Language (Deutscher 2005) are overviews of grammaticalizations that have been documented across languages, including from nouns to adjectives, case markers, adpositions, adverbs, and complementisers; from verbs to aspect markers, case markers, adpositions, complementisers, demonstratives, and negative markers; from demonstratives to definite articles, relative clause markers, and pronouns; and from pronouns to agreement and voice markers.

These pathways of change by which new categories can be created are the fullest account of the evolution of language that we currently have, a fraction of which are summarised in a tree below from Heine and Kuteva (2008:111). They help us make sense of the inherent fuzziness of closely related categories, and also the formal similarities between them, including correlations in their word orders. Word order universals may turn out to have been shaped in part by other factors such as processing and learnability, but they also tell the story of a linguistic equivalent of the Tree of Life, the history of grammatical categories.

(References: see this bibliography. *Correction: it was pointed out to me that the Thai example that I cited from memory and without a source was wrong, which I've now replaced with the example of Egyptian Arabic from WALS.)

The author writes: <>

ReplyDeleteI am unaware of any studies demonstrating that ideophones are 'invented out of nothing'. Examination of thousands of ideophones in many Bantu languages, for example, shows etymological relationship to normal verb roots, often with added specialized ideophonic suffixes. In other cases ideophones appear to be based on borrowings (such as for example many click-initial ideophones in Zulu coming from Khoi-San languages). Even when new roots are formed it seems to be on the basis of preexisting phonosemantic partials.