New paper on language macro-families, from Austro-Tai to Indo-European-Chukotko-Kamchatkan

A new paper was published three days ago in PNAS by Gerhard Jäger on language macro-families, to add to Annemarie Verkerk's list of phylogenetic linguistics papers that have appeared this month. I give here both a couple of encouraging results from the paper (mainly statistical support for the Austro-Tai hypothesis), and a couple of criticisms (mainly of the parsimony-based method of constructing the phylogeny).

One of the greatest achievements of linguistics has been the discovery of large language families. Some 583 languages of Europe and India from English to Nepali have been demonstrated to be descendants of a single common language, Proto-Indo-European. A further 1274 languages spread around the Pacific and the Indian Ocean from Madagascar to Hawaii have been shown to be descended from a single language spoken in Taiwan, Proto-Austronesian.

The 7-8000 languages of the world described so far have been placed into roughly 430 large groups of this type (37 in Eurasia alone), according to Glottolog. These families are defined by shared innovations in basic vocabulary (such as English brother, Latin frater, Russian brat etc.). Linguists dream of being able to link these language families into even larger units, and push back our knowledge of language history further back in time. With more distantly related languages however, it becomes hard to distinguish these patterns from accidental similarity, or recent borrowing of loanwords, which confounds our ability to find more distant connections between languages. Not that people have not tried doing this. These attempts range from interesting,

The 7-8000 languages of the world described so far have been placed into roughly 430 large groups of this type (37 in Eurasia alone), according to Glottolog. These families are defined by shared innovations in basic vocabulary (such as English brother, Latin frater, Russian brat etc.). Linguists dream of being able to link these language families into even larger units, and push back our knowledge of language history further back in time. With more distantly related languages however, it becomes hard to distinguish these patterns from accidental similarity, or recent borrowing of loanwords, which confounds our ability to find more distant connections between languages. Not that people have not tried doing this. These attempts range from interesting,

The above database is claiming that English man, Mandarin Chinese 男 nán 'male', Ancient Egyptian mn 'shepherd', Chechen naχ 'man', Yeniseian hīɣ 'man', and so on are sufficiently similar that they may be inherited from a common ancestor. A claim like this in fact has nothing wrong with it in principle, except that most of the time, this type of work does not demonstrate that these patterns are not simply accidental. As Steven Pinker put it in The Language Instinct (1994:255),

I have no problem with

Greenberg’s use of many loose correspondences, or even with the fact that some

of his data contains random errors. What

bothers me more is his reliance on gut feelings of similarity rather than on

actual statistics that control for the number of correspondences that might be

expected by chance…Though I am willing to be patient with Nostratic and similar

hypotheses pending the work of a good statistician with a free afternoon, I

find the Proto-World hypothesis especially suspect. (Comparative linguists are speechless.)

The new paper by Gerhard Jäger could therefore be viewed as one such work by a good statistician with a free afternoon - although the ASJP database which it uses is a project that has been developing for many years, containing basic vocabulary wordlists for about 4400 languages. Jäger's paper used these wordlists to compute how similar languages are in their basic vocabulary, and see whether particular language macro-families emerge.

I had assumed that it already had been tested by the makers of the ASJP database (e.g. these trees) and had yielded negative results. I was therefore surprised by the main claim of the paper: that there is strong support when you do this for several controversial macro-families raised in the literature. These include Austronesian being related to Tai-Kadai (Austro-Tai), Mongolic being related to Tungusic and Turkic (Altaic), and even some form of 'Eurasiatic' subsuming Indo-European, Uralic, Altaic and some language families of Siberia.

The paper takes word lists from 1,161 languages in Eurasia. It then computes the similarity of words between each language; for example, it turns out that the Irish Gaelic klox 'stone' has a short edit distance to the word kox 'stone' in Northern Itelmen, a Chukotko-Kamchatkan language in far eastern Siberia. These distances are computed for each word in the forty-word list, and a total distance between languages is then computed. By assuming that closely related languages are likely to be more similar, a tree can be constructed using a 'greedy minimal evolution' algorithm that puts more similar languages together in clades. Most known language families are successfully recovered using this data and method.

An interesting feature of the way that distances are computed is that similarities are weighted by sound class. For example, hand in English is distant from mano in Spanish because the difference between h and m at the beginning of the word is large, whereas differences in vowels are penalized less. In addition, the distances between words are corrected by how similar the languages are in the sounds that they use; English and Dutch use similar sound classes for example, and hence the likelihood of English and Dutch words resembling each other by chance is higher. This is then corrected for when computing distance (interestingly, genuinely related languages are therefore penalized from the outset by virtue of having more similar sound systems).

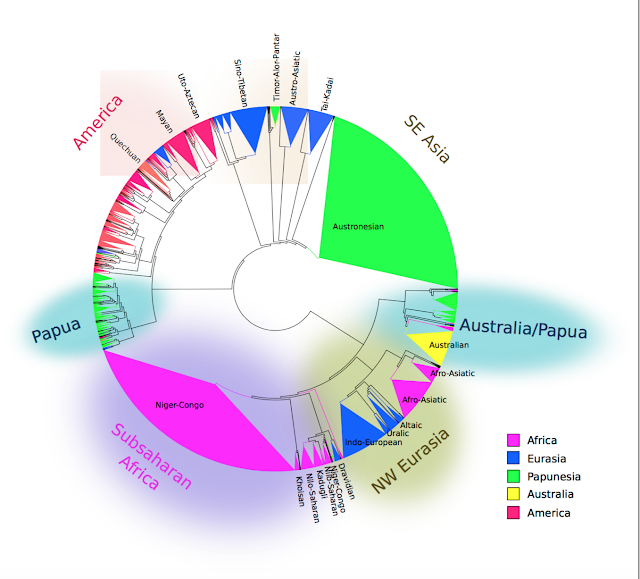

These innovations in the method are ostensibly the reason for the new improved results. Above the level of known language families, it turns out that there are larger units, some with high confidence values. The resulting tree looks like this:

It turns out that the closest relative of Indo-European is Chukotko-Kamchatkan, an answer nobody would have predicted given that Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages are spoken in far eastern Siberia. Part of the explanation for this geographically implausible clade may be the 'surprisingly high number' of chance resemblances between Celtic and Chukotko-Kamchatkan words (c.f. the Irish and Northern Itelmen for 'stone' above), which Jäger gives an extended discussion of. Indo-European turns out to be part of a large family spanning northern Eurasia, from the Urals to Mongolia, and up to eastern Siberia opposite Japan.

These are interesting results, and I don't know what people will make of them (I haven't seen any coverage or responses so far, in contrast with Mark Pagel et al.'s more publicized paper in 2013, also in PNAS). For what it's worth, here are in my opinion two good findings from the paper:

i) Austro-Tai. Several linguists have claimed that the evidence for Austronesian and Tai-Kadai being related is very strong. As I've written in a previous blogpost, linguists such as Sagart and Ostapirat provide shared vocabulary as evidence but do not back it up with a statistical test by comparing them with other randomly selected languages. It is therefore very interesting that Austronesian and Tai-Kadai come out as a strongly supported clade when such a test is done. This is also an impressive result given how different the phonological systems are of Austronesian and Tai-Kadai languages. It could still be partially due to borrowing, a question that could be answered by looking at what types of words are similar, as some words are known to be more likely to be borrowed than others.

ii) Less spectacularly, there are several geographically plausible macro-families, which could also simply be due to recent borrowing. Examples include Sino-Tibetan/Hmong-Mien, Tungusic/Mongolic, and Ainu/Japanese. This is still interesting, and shows the validity of the method in detecting genuine similarity in vocabulary between languages. It only means that our methods for distinguishing inheritance from borrowing need to improve.

And here are two weaknesses of the paper:

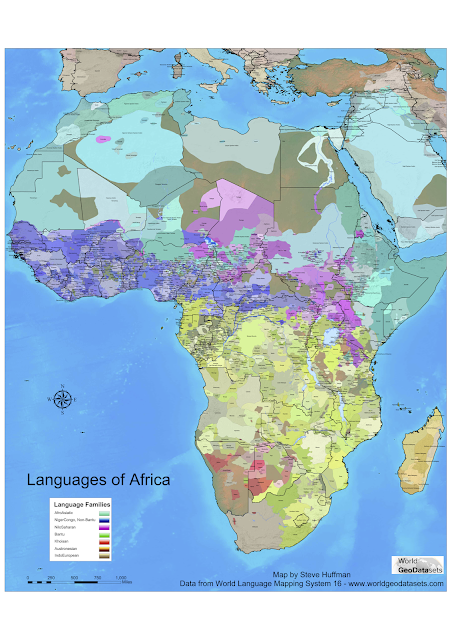

i) He chooses to test only languages of Eurasia, without giving any justification. A much fairer test would be to pick language families from around the world. The reason is that by picking language families of Eurasia, he is reducing the chance of finding language macro-families that are even more stretched than Indo-European-Chukotko-Kamchatkan. If several Eurasian families turned out to be related most closely to language families of New Guinea or South America, for example, then this would cast doubt on how well the method really works. As it stands, by testing only Eurasian language families, even the oddest macro-families (Ainu and Austro-Asiatic, Indo-European and Chukotko-Kamchatkan) can be argued away as not being completely impossible.

ii) The 'greedy minimal evolution' method of constructing the phylogeny. For various reasons this method is too crude. With a lot of language change, languages end up becoming similar by accident, such as the Celtic and Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages mentioned above. Conversely, with a lot of language change, related languages can end up being very different from each other. An algorithm that relates languages on the basis of similarity is therefore likely to confuse degree of relatedness with amounts of change (branch-lengths in the tree).

A better method is Bayesian phylogenetic inference, which tries out different trees and allows the branch lengths to vary, so that languages may be related but have been diverging for a long time, causing them to be not very similar. Languages which are overall quite dissimilar can nevertheless turn out to be related if they have a few resemblances in the most slow-changing words, if these words are not shared by other languages.

The solution is therefore to recognize that words change at different rates depending on how frequent they are (for example, forms for 'two' such as deux, dva, do, due etc. in Europe are retained from Proto-Indo-European). Instead of computing the overall distance between languages, an algorithm that allows words to change at different rates is clearly going to capture genuine relatedness more effectively. Simulating the development of individual words also allows us to work out which ones are more likely to be borrowed and which ones are likely to be inherited. Jäger points out the need for more work on simulating language contact, and also the interesting prospect of modeling the way that sounds change and using more informative comparison of words that way (as Johann-Mattis List's package in Python Lingpy does). Another promising approach is to take semantic change into account and use a larger lexicon (e.g. Tier 'animal' in German is cognate with deer in English), perhaps by computing semantic distance between words using semantic vectors.

All of these are possible improvements to the methodology of the paper, some of which Jäger notes in conclusion. Despite these weaknesses so far, this paper is probably the best work in showing that this kind of long distance comparison is possible. It compares favorably to Mark Pagel et al.'s PNAS paper in 2013, which used putative cognates from the Tower of Babel (the database mentioned above that claims that Ancient Egyptian mn and English man may be related) to suggest that they were evidence for a Eurasiatic family. They justified the validity of these long-distance etymologies by showing that the meanings of these words ('I', 'you', 'mother' etc.) tended to be highly frequent words in everyday speech, exactly what you would expect of words conserved over thousands of years. The finding by itself I don't think is necessarily very useful, as it could simply show that the makers of the Tower of Babel have a bias towards looking for shared word forms that are more basic and more frequent, such as pronouns, numerals, demonstratives and everyday nouns, the kind of words which would make plausible ancient cognates.

Pagel et al.'s paper is however interesting for calculating the half-life of words, namely the number of years before a word is typically replaced in a language; for example, words for 'I' seem to have a 50% chance of being replaced after as much as 77,000 years, based on the amount that these words have changed within known families. This latter fact suggests that some words may indeed be conserved from ancestral languages many thousands of years ago. In some respects that paper is the opposite in methodology to Jäger's, its strength being in the way that it studied the different rates of change of words rather than calculating distance between whole wordlists, but its weakness being in not evaluating how likely the Tower of Babel project is to find similarities in word forms due to chance.

Apart from these improvements to methodology, the main work in the future will be more vocabulary data collection, which besides the ASJP database is now being done by Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson and others in the 'Glottobank' project, building on work in specific regions such as the Indo-European Cognacy Database, the Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database and the Trans-New Guinea database.

Jäger's paper is encouraging in showing that such long-distance comparisons seem to be possible, and that the main challenges are in collecting data and refining these statistical techniques. I am excited in particular by the prospect that these methods in the short-term will allow us to replace the Austronesian family with the larger Austro-Tai family - a massive family of over 500 million speakers that connects Thai and Lao speakers and their rice-farming origins in southern China with the great seafaring migrations of Austronesians out into the Pacific.

I had assumed that it already had been tested by the makers of the ASJP database (e.g. these trees) and had yielded negative results. I was therefore surprised by the main claim of the paper: that there is strong support when you do this for several controversial macro-families raised in the literature. These include Austronesian being related to Tai-Kadai (Austro-Tai), Mongolic being related to Tungusic and Turkic (Altaic), and even some form of 'Eurasiatic' subsuming Indo-European, Uralic, Altaic and some language families of Siberia.

The paper takes word lists from 1,161 languages in Eurasia. It then computes the similarity of words between each language; for example, it turns out that the Irish Gaelic klox 'stone' has a short edit distance to the word kox 'stone' in Northern Itelmen, a Chukotko-Kamchatkan language in far eastern Siberia. These distances are computed for each word in the forty-word list, and a total distance between languages is then computed. By assuming that closely related languages are likely to be more similar, a tree can be constructed using a 'greedy minimal evolution' algorithm that puts more similar languages together in clades. Most known language families are successfully recovered using this data and method.

An interesting feature of the way that distances are computed is that similarities are weighted by sound class. For example, hand in English is distant from mano in Spanish because the difference between h and m at the beginning of the word is large, whereas differences in vowels are penalized less. In addition, the distances between words are corrected by how similar the languages are in the sounds that they use; English and Dutch use similar sound classes for example, and hence the likelihood of English and Dutch words resembling each other by chance is higher. This is then corrected for when computing distance (interestingly, genuinely related languages are therefore penalized from the outset by virtue of having more similar sound systems).

These innovations in the method are ostensibly the reason for the new improved results. Above the level of known language families, it turns out that there are larger units, some with high confidence values. The resulting tree looks like this:

It turns out that the closest relative of Indo-European is Chukotko-Kamchatkan, an answer nobody would have predicted given that Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages are spoken in far eastern Siberia. Part of the explanation for this geographically implausible clade may be the 'surprisingly high number' of chance resemblances between Celtic and Chukotko-Kamchatkan words (c.f. the Irish and Northern Itelmen for 'stone' above), which Jäger gives an extended discussion of. Indo-European turns out to be part of a large family spanning northern Eurasia, from the Urals to Mongolia, and up to eastern Siberia opposite Japan.

These are interesting results, and I don't know what people will make of them (I haven't seen any coverage or responses so far, in contrast with Mark Pagel et al.'s more publicized paper in 2013, also in PNAS). For what it's worth, here are in my opinion two good findings from the paper:

i) Austro-Tai. Several linguists have claimed that the evidence for Austronesian and Tai-Kadai being related is very strong. As I've written in a previous blogpost, linguists such as Sagart and Ostapirat provide shared vocabulary as evidence but do not back it up with a statistical test by comparing them with other randomly selected languages. It is therefore very interesting that Austronesian and Tai-Kadai come out as a strongly supported clade when such a test is done. This is also an impressive result given how different the phonological systems are of Austronesian and Tai-Kadai languages. It could still be partially due to borrowing, a question that could be answered by looking at what types of words are similar, as some words are known to be more likely to be borrowed than others.

ii) Less spectacularly, there are several geographically plausible macro-families, which could also simply be due to recent borrowing. Examples include Sino-Tibetan/Hmong-Mien, Tungusic/Mongolic, and Ainu/Japanese. This is still interesting, and shows the validity of the method in detecting genuine similarity in vocabulary between languages. It only means that our methods for distinguishing inheritance from borrowing need to improve.

And here are two weaknesses of the paper:

i) He chooses to test only languages of Eurasia, without giving any justification. A much fairer test would be to pick language families from around the world. The reason is that by picking language families of Eurasia, he is reducing the chance of finding language macro-families that are even more stretched than Indo-European-Chukotko-Kamchatkan. If several Eurasian families turned out to be related most closely to language families of New Guinea or South America, for example, then this would cast doubt on how well the method really works. As it stands, by testing only Eurasian language families, even the oddest macro-families (Ainu and Austro-Asiatic, Indo-European and Chukotko-Kamchatkan) can be argued away as not being completely impossible.

ii) The 'greedy minimal evolution' method of constructing the phylogeny. For various reasons this method is too crude. With a lot of language change, languages end up becoming similar by accident, such as the Celtic and Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages mentioned above. Conversely, with a lot of language change, related languages can end up being very different from each other. An algorithm that relates languages on the basis of similarity is therefore likely to confuse degree of relatedness with amounts of change (branch-lengths in the tree).

A better method is Bayesian phylogenetic inference, which tries out different trees and allows the branch lengths to vary, so that languages may be related but have been diverging for a long time, causing them to be not very similar. Languages which are overall quite dissimilar can nevertheless turn out to be related if they have a few resemblances in the most slow-changing words, if these words are not shared by other languages.

The solution is therefore to recognize that words change at different rates depending on how frequent they are (for example, forms for 'two' such as deux, dva, do, due etc. in Europe are retained from Proto-Indo-European). Instead of computing the overall distance between languages, an algorithm that allows words to change at different rates is clearly going to capture genuine relatedness more effectively. Simulating the development of individual words also allows us to work out which ones are more likely to be borrowed and which ones are likely to be inherited. Jäger points out the need for more work on simulating language contact, and also the interesting prospect of modeling the way that sounds change and using more informative comparison of words that way (as Johann-Mattis List's package in Python Lingpy does). Another promising approach is to take semantic change into account and use a larger lexicon (e.g. Tier 'animal' in German is cognate with deer in English), perhaps by computing semantic distance between words using semantic vectors.

All of these are possible improvements to the methodology of the paper, some of which Jäger notes in conclusion. Despite these weaknesses so far, this paper is probably the best work in showing that this kind of long distance comparison is possible. It compares favorably to Mark Pagel et al.'s PNAS paper in 2013, which used putative cognates from the Tower of Babel (the database mentioned above that claims that Ancient Egyptian mn and English man may be related) to suggest that they were evidence for a Eurasiatic family. They justified the validity of these long-distance etymologies by showing that the meanings of these words ('I', 'you', 'mother' etc.) tended to be highly frequent words in everyday speech, exactly what you would expect of words conserved over thousands of years. The finding by itself I don't think is necessarily very useful, as it could simply show that the makers of the Tower of Babel have a bias towards looking for shared word forms that are more basic and more frequent, such as pronouns, numerals, demonstratives and everyday nouns, the kind of words which would make plausible ancient cognates.

Pagel et al.'s paper is however interesting for calculating the half-life of words, namely the number of years before a word is typically replaced in a language; for example, words for 'I' seem to have a 50% chance of being replaced after as much as 77,000 years, based on the amount that these words have changed within known families. This latter fact suggests that some words may indeed be conserved from ancestral languages many thousands of years ago. In some respects that paper is the opposite in methodology to Jäger's, its strength being in the way that it studied the different rates of change of words rather than calculating distance between whole wordlists, but its weakness being in not evaluating how likely the Tower of Babel project is to find similarities in word forms due to chance.

Apart from these improvements to methodology, the main work in the future will be more vocabulary data collection, which besides the ASJP database is now being done by Russell Gray and Quentin Atkinson and others in the 'Glottobank' project, building on work in specific regions such as the Indo-European Cognacy Database, the Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database and the Trans-New Guinea database.

Jäger's paper is encouraging in showing that such long-distance comparisons seem to be possible, and that the main challenges are in collecting data and refining these statistical techniques. I am excited in particular by the prospect that these methods in the short-term will allow us to replace the Austronesian family with the larger Austro-Tai family - a massive family of over 500 million speakers that connects Thai and Lao speakers and their rice-farming origins in southern China with the great seafaring migrations of Austronesians out into the Pacific.

|

| Dai village near Menghai in southwest China |

|

| Map of Austronesian migrations in the Pacific (with Hedvig and Damian Blasi in the Auckland Museum) |

Dear Jeremy,

ReplyDeletea significant correction: all of the examples that you attribute to "The Global Lexicostatistical Database" have, in fact, nothing to do with lexicostatistics and are taken not from the GLD, but from its old "mother site", "The Tower of Babel", a set of etymological (not lexicostatistical!) databases both for commonly accepted families and for their much more hypothetical groupings into macro-families.

The Global Lexicostatistical Database (http://starling.rinet.ru/new100/main.htm) is linked (where possible) to The Tower of Babel, but it is in fact a completely autonomous and self-sufficient project whose primary units of data are Swadesh wordlists for the world's languages rather than etymological comparisons. I am mentioning this, in particular, because it might seem odd to readers of the blog that a tentative "global comparison" like 'man' would have anything to do with lexicostatistics (and, in fact, it does not). Therefore, it would be nice if you could change all references to the GLD in this post to "Tower of Babel".

Yours

George Starostin

Thanks for the correction, I've amended it.

Delete