Workshop in Jena on Austronesian linguistics, archeology and genetics

Last week at the new MPI for the Science of Human History in Jena, there was a two-day workshop on the peopling of island Southeast Asia and the Pacific, organised by Russell Gray, Lisa Matisoo-Smith and Simon Greenhill. It was divided between talks on archeology, linguistics and genetics, with a couple of others on computational modeling from anthropology and ecology. The titles and abstracts of talks are here. Here is my brief and perhaps slightly garbled summary of the talks.

Archeology

Bob Blust said in his talk that linguistics can make predictions for archeology, such as the presence of Neolithic rice remains in Taiwan, because Austronesian languages originated in Taiwan, and Proto-Austronesian is reconstructed as having many terms for rice. This prediction turned out to be vindicated, such as by japonica rice grains found at the 4500-5000 BP site at Dabenkeng. In this spirit, some archeology talks were on migrations which we know happened from linguistics, but where the archeological evidence for these migrations has so far been elusive. Nicole Boivin talked on her research in Madagascar, which looked at the dating of plant species which came from Asia to Africa (such as bananas), as well as various animal species such as rats, and discussed the suggestion that migrations to Madagascar would have gone along the east coast of Africa. She has a blog (with various other authors) on the prehistory of the Indian Ocean here.

Several talks such as Christophe Sand's were on the complexity of Pacific migrations from the point of view of Lapita pottery in Melanesia and Polynesia. David Burley talked on when and where Polynesians became 'Polynesian', archeologically speaking - apparently the answer is precisely at Nukuleka on Tonga, 2838 ± 8 years ago (see this paper). Michiko Intoh talked about Fais island, a raised coral island (pictured) where arrivals of people several hundred years apart were documented by objects they left behind (such as in evolving styles of fish hook and pottery), engagingly illustrated by a slide showing overlapping layers of different remains in one site.

Linguistics

These talks ranged from questions of the details of the Austronesian family, to controversial proposals of relations with Tai-Kadai and interactions with Japanese. An example of the former were Emily Gasser's reconstruction of the South Halmahera‐West New Guinea subgroup, the little-understood sister of the Oceanic languages, and Bethwyn Evans on language contact in southern Bougainville.

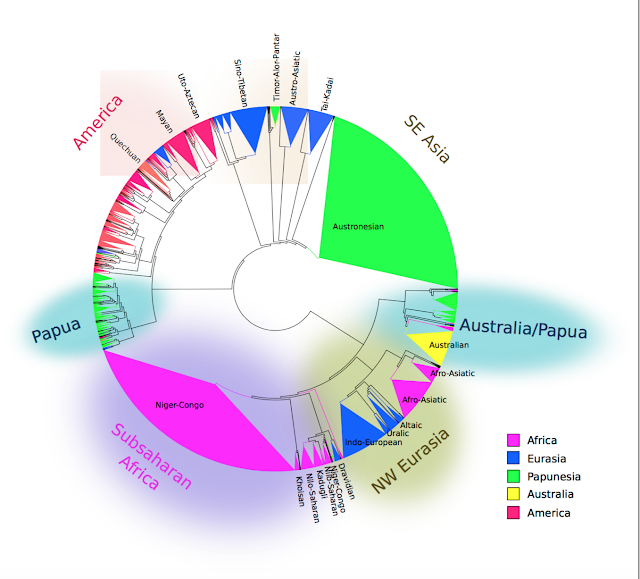

Simon Greenhill showed the latest version of a consensus tree of Austronesian languages, using lexical data and Bayesian phylogenetic methods. Malcolm Ross discussed differences between his proposed tree and Simon Greenhill's. Ross's tree was based on different data, namely phonological innovations and some morphological or other idiosyncratic information, whereas Greenhill's trees - in the plural, because Bayesian methods give a posterior distribution of trees with different likelihoods for different clades, although summarized visually by a consensus tree - are based on cognate coding of vocabulary. Bayesian inference can also be applied to Ross's data on innovations, which would be good to see.

A recurring theme in the linguistics talks was language contact and 'linkages'. Trees work in biology because once species diverge, they do not influence each other genetically again (with exceptions such as hybridization and horizontal gene transfer in bacteria). Languages influence each other horizontally, and hence a perennial objection to phylogenetic methods is that language evolution is not really tree-like, but network-like. Alex François proposed method of analyzing languages by showing linkages between them, i.e. cognates could be shared between languages but these groupings could be overlapping (e.g. languages A and B share innovations, while B and C also share innovations, defying any neat clustering of two languages together). He showed his data from languages in Vanuatu to illustrate the point.

As some people remarked, this does not amount to much more than a visualization technique for the data (similar to a Neighbour Net), showing which cognates are found where, without any attempt to work out probabilistically what generated the data. Mattis List said the data 'cried out for historical interpretation', namely working out when these different cognate sets could spread and what the most likely paths of transmission were. Simon Greenhill talked about this issue as well, analyzing data in Indo-European and Austronesian languages for whether it was tree-like or more random, using delta scores (a number between 0 and 1, with 0 being the tidiest and most tree-like and between 0.5 and 1 being random); Polynesian languages were on the random end of the scale, but Vanuatu was relatively tidy, contrary to Alex François's picture of the data. Although I liked the comparison of tree-like and random evolution, a fairer test would be to simulate what type of data a linkage would produce: it might produce a low delta score, because languages share vocabulary if they are geographically neighboring, potentially giving the illusion of tree-like history.A recurring theme in the linguistics talks was language contact and 'linkages'. Trees work in biology because once species diverge, they do not influence each other genetically again (with exceptions such as hybridization and horizontal gene transfer in bacteria). Languages influence each other horizontally, and hence a perennial objection to phylogenetic methods is that language evolution is not really tree-like, but network-like. Alex François proposed method of analyzing languages by showing linkages between them, i.e. cognates could be shared between languages but these groupings could be overlapping (e.g. languages A and B share innovations, while B and C also share innovations, defying any neat clustering of two languages together). He showed his data from languages in Vanuatu to illustrate the point.

There were some more controversial linguistic ideas in other talks. Laurent Sagart and Weera Ostapirat talked about the theory that Tai-Kadai and Austronesian are related. For Sagart, this means that Tai-Kadai is a branch of Austronesian, and for Ostapirat, this means that they are sister languages which split in China.

Although their data seems compelling, I would like to see a proper statistical demonstration of the relationship. Sagart said that there is 'no doubt' about the Austro-Tai relationship - but how much is no doubt? Is there a 5%, 1%, 0.001% or 49% probability that he and Ostapirat are wrong? A simple test is to see whether applying their search for cognates to twenty randomly selected languages could generate similarly compelling results. If it turns out that there are in that sample languages such as Meso-American languages which have a similarly large number of 'cognates' with Austronesian, then the Austro-Tai relationship is spurious. Another test is permuting the Tai-Kadai data, controlling for word length, and seeing how many 'cognates' there are with Austronesian then. It is not as if this has not been tried (Mattis List for example has analyzed some proposed Austro-Tai cognates), but I find it surprising that this is not already a standard part of such arguments.

A similarly controversial idea (at least for me) was that languages in northern Eurasia form a 'Transeurasian' family (previously called Altaic), and that Japanese and Korean are part of it. Martine Robbeets talked about how a scenario of Transeurasian languages splitting in northeast Eurasia and going into the Korean peninsula and then Japan may be supported by archeological evidence. She didn't present linguistic evidence of Japanese and other 'Transeurasian' languages being related, so I asked for it in the questions. Apparently her PhD thesis shows that after factoring out known borrowings, there are many monomorphemic terms which show cognacy, and in fact apparently strict sound correspondences, which if correct would be a good statistical demonstration of the relationship. I think an additional promising approach in this case is phylogenetics using language structures - Japanese and other languages of northern Eurasia show striking typological similarities, such as similar word orders, which are unlikely to be all due to recent contact given their high stability in other families (c.f. Dunn et al. 2011).

Mattis List talked about 'the future of the comparative method', using methods (again partly inspired by methods in biology) of aligning proposed cognates, and encouraging collaboration between people who are able to implement these computational methods and more traditional historical linguists.

Mattis List talked about 'the future of the comparative method', using methods (again partly inspired by methods in biology) of aligning proposed cognates, and encouraging collaboration between people who are able to implement these computational methods and more traditional historical linguists.

Finally, Paul Sidwell presented on Austro-Asiatic, modeling the history of the family using a large database of lexical data. His phylogenetic analysis with Greenhill and Gray suggests that the family originated 5000 years before present, meaning that it is likely from archeological evidence to have begun in southern China - a new and unexpected result. It would be wonderful to see this vindicated by phylogeography à la Bouckaert et al.'s work on Indo-European: it is a good test case, because there are no Austro-Asiatic languages in southeastern China, but we know archeologically and genetically that if Austro-Asiatic is 5000 years old, then it is likely to have been there, as rice terms are reconstructed in proto-Austro-Asiatic and japonica rice farming was only in southern China at the time. This is a case of archeology and genetics providing a challenge for linguistic work, or in this case, for the use of lexical data and phylogeography.

The genetics talks opened up interesting comparisons for both archeology and linguistics. Albert Ko talked on ancient DNA from a 8200 year old skeleton in Taiwan, the Liangdao man (pictured above, from his paper here). He also described the rapid expansion from the north of Taiwan to the south, reconstructed from mitochondrial DNA. Interestingly, when he compared mitochondrial DNA from Tai-Kadai speakers, he did not find any particularly close relationship with Austronesian speakers in Taiwan. I asked about the samples - he used Thai speakers rather than say Tai speakers from southern China, and Cambodians for the Austro-Asiatic family rather than Palaungic speakers - and various people pointed out that data from southern China would be more relevant for testing genetic links that might confirm or disconfirm an Austro-Tai hypothesis. Frederique Valentin compared genetics and archeology in her talk, as human skeletons associated with the Lapita culture were previously concluded to be too distant from modern Polynesians genetically to be their real ancestors, indicating the importance of later expansions overriding the first ones.

One revelation for me was Lisa Matisoo-Smith's talk on the genetic histories of chickens, rats, pigs and dogs in the Pacific, which can all be tracked because these animals were brought in boats by Austronesian speakers; they show both fairly congruent histories and hint at the complexity of movements that we do not understand yet. Irina Pugach talked on the genetic history of islands such as Santa Cruz and the ability to use genome-wide data to time the arrival of people in different places.

A more controversial talk was the question of whether the Austronesians reached South America, discussed by Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas. There were a couple of clearly Polynesian skulls found in Brazil; unfortunately, once they were dated and various corrections applied, they seem to be post-Columbian, meaning they could have come over with Europeans. People also expressed skepticism that Polynesians would get to Brazil (rather than say Peru or Chile); worse, there was no native American admixture at all, and some people even suggested that the skulls might have been misclassified. A follow-up study on this question was on Native American admixture on the island of Rapanui, which however could have been due to Europeans coming to Rapanui from South America having previously had admixture with Native Americans.

An intriguing talk by Steven Lansing was on correlations between languages and mitochondrial DNA lineages in Indonesia. These correlations last a very long time, even through language shift, in some cases over 10,000 years (far older than the age of Austronesian): correlations like these could be caused by groups of related speakers all shifting together, suggesting that linguistic communities can be highly stable, in the sense of human lineages staying in one place and speaking the same language. In the case of the Austronesian languages, the correlation is with mitochondrial DNA (which people inherit from their mother), because communities are matrilocal. In the two patrilocal communities, there was a weak correlation between language and Y chromosome DNA, but not outside of those two communities.

Computational Models

One of the more exciting aspects of the conference was computational modeling. A talk by Adam Powell illustrated this, unveiling his program 'Demigod' for simulating population expansions, which you could constrain using linguistic and archeological data; the program would then simulate what the genetic data of a hypothetical expansion would look like, which can then be compared to real data.

Another computer model was Adrian Bell's model of how people may have sailed through the Pacific, weighing different factors such as wind direction and arbitrary choice of where to sail ('where to point your canoe'), and comparing his simulations with known dates for the settlement of different islands (if I understood the result correctly, arbitrary direction of sailing was the main determinant of how migrations happened).

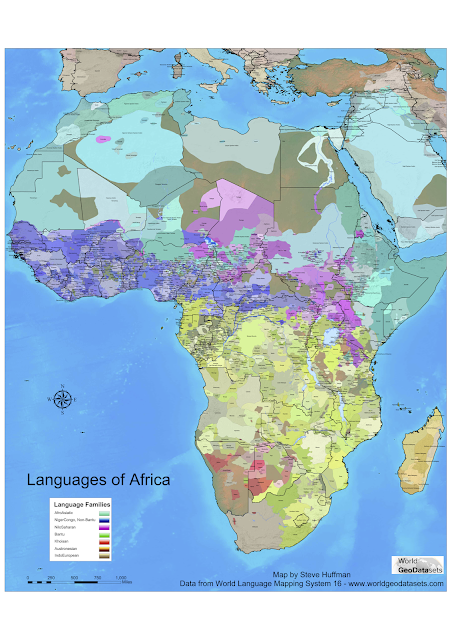

Michael Gavin presented models for predicting numbers of languages in different places; for example, Australia has 440 languages, while some Pacific islands such as Vanuatu have over a hundred languages (and other such as Samoa only a few). There seem to be ecological constraints on language diversity, such as the amount of rainfall in different parts of Australia, and the size of islands, which seem to be good so far at predicting patterns of language diversity.

Russell Gray in his summing up of the first day said that we should try to quantify certainty between disciplines, and that one way of doing this is by modeling; modeling the certainty of your findings, especially when communicating with people from another discipline, is the way to resolve discrepancies in interpretation, such as how likely the Austro-Tai hypothesis is to be correct, or how likely absence of archeological evidence for a migration (for example) is evidence that that migration did not happen. People present their findings with a certain degree of confidence (c.f. Sagart saying - admittedly over coffee in the break - that there is 'no doubt' about the Austro-Tai relationship), but without some attempt at quantification, the confidence that people have in their own results is almost meaningless. Modeling these probabilities is hard work, as it involves simulating real-world scenarios, such as the way that historical linguists analyze data (e.g. the probability of a historical linguist comparing cognates and coming up with a compelling case for Austro-Tai where there is in fact no relationship), or the way that people leave behind artifacts and other remains in migrations. Nevertheless, this work is arguably necessary to show confidence of findings more objectively, and is useful as an exercise in its own sake, as a way of showing how well we understand different real-world scenarios and the patterns of data that they produce.

I see another use for modeling, which is to integrate the data such as that presented at this workshop; rather than let accumulated knowledge sit in different disciplines, what I would like to see is a model which archives everything that we know about Pacific migrations. This type of model is anathema to some people, who see modeling as a way of simplifying reality, where we can change a few parameters in order to assess how well it works. If a model is too complicated, then it is difficult to evaluate how likely it is to reflect reality. This is one approach, but I see room for building up a simulation for its own sake, showing what we believe happened, as an archive of data rather than a method of testing simplified hypotheses; a virtual reality model of history that can be built up to be increasingly detailed, and hopefully increasingly realistic.

Comments

Post a Comment