Why should we care about languages that are dying?

Linguist John McWhorter wrote recently in the New York times on the topic of why should we care if 90% of languages that are alive today perish within a very short time span. Go read the article, it's a very good read.

I'll do a brief sum-up here and then present my own thoughts. The text is 911 words and I doubt that McWhorter has exhausted all his reflections on this topic, let's just keep that in mind. In this text he answers a frequently asked question "if indigenous people want to give up their ancestral language to join the modern world, why should we consider it a tragedy?". This is a common question face by linguists, and a very important one that should be addressed with great care and respect.

He dismisses the earlier linguistic-relativist argument he used to put forward, i.e. that each language represent a different world view and therefore another way for us as a collective human society of viewing the world.

Now, he rather puts forward two other arguments:

1) languages are important markers of community and identity, when people lose their languages they lose their culture and history.

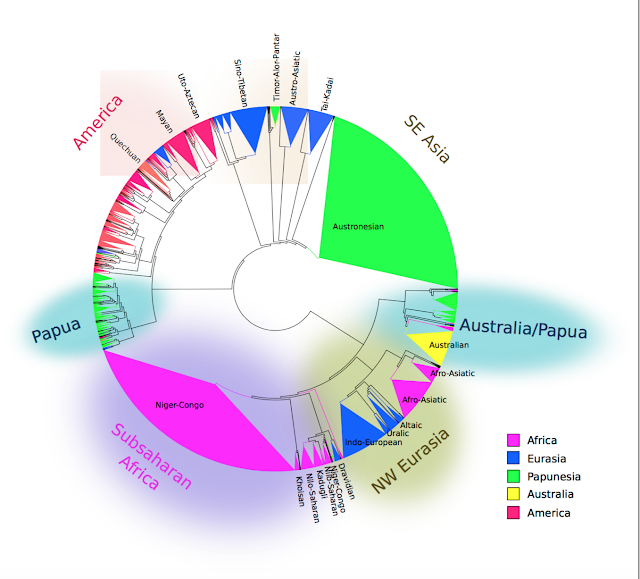

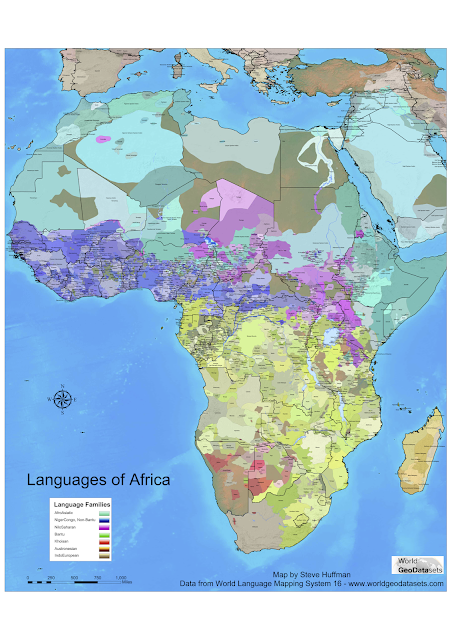

2) He writes languages are scientifically interesting even if they don’t index cultural traits. They offer variety equivalent to the diversity of the world’s fauna and flora.

In other words, even if the linguistic relativism part of linguistic diversity isn't interesting, the basic question of linguistic typology is. I've made an attempt at formulating that question by myself, based offa Hjelmslev and Boas, I can't know if this is what McWhorther is interested in. Here we go:

In order to understand ourselves as a species better we need to study what we can do, what diversity we are capable of.

McWhorther then finishes with:

These are the arguments I have ready for the “Why should we care?” fellow these days. We should foster efforts to keep as many languages spoken as possible, and to at least document what the rest of them are like. Cultures, to be sure, show how we are different. Languages, however, are variations on a worldwide, cross-cultural perception of this thing called life.

To me, there are two very important things missing here. Firstly, the agency of the communities. We cannot as linguists, and certainly not as non-members of the communities, make predictions about what they want. We can let them know that their language is

a) a language (at all), this is sometimes misunderstood

b) equal to other languages

c) interesting

Just like all other languages it deserves a dictionary, a grammar, pedagogical books, a place in the political system etc. That we can do, that we can say. The public often seems ignorant of the fact that all languages are equal.

Languages with more speakers or more written down literature are by now means more valuable or better. This is a fact I find that I need to explain often, once to a frenchman who claimed that french was the only language with which philosophy could be discussed. Sigh. Another time it was someone who thought that the reason that English was spoken by so many was because it had traits that were just more optimal for communication. In answer to that question I recommend looking at this map of "Countries the UK has not invaded" and then have a long hard think.

If explaining this and showing interest gives communities more power and confidence, great. But we cannot tell them that they should be doing this or that. It is not our right. In Swedish we would call this to remove someone's "myndighet". Their right and competence to govern themselves. Imma Trekkie, so I can't help but think of some of the moral dilemma episodes where humans get put in zoos to be studied by much more advances alien beings. We can't be guilting people for having to live in a world where their standard of life, and the standard of life for their families, will often increase significantly if they learn the majority language of their region.

I don't think this is what linguists do, nor what McWhorter is proposing, but I think it's worth keeping in mind. The fact that languages are dying are tied together with larger patterns of urbanisation, cultural colonialism etc. You might wanna read this study on correlations between linguistic diversity and ecnomonic growth. We can do what we can in stressing the fact that all languages are equal and that we, as well-educated people with authority, find them all interesting to study. By doing that perhaps we can instill confidence and/or have an effect on the political struggle of that community. It's sad and crass, but by discussing matters like this as privileged people our voices sometimes can make a greater difference compared to the voices of the actual communities than we perhaps wish they would.

As for the second argument, if that was true then we need just document and study all languages currently spoken and then we need not care whether they live or die. That is not an answer to the question "why should we care that they are dying?", it's answering the question "why should we care that they are dying before we can extract all new information from them?".

Add to this line of thought the fact that 7 000 languages is actually not enough if we want to answer the larger typological question outlined above. Let's just do a quick count. Humans have spoken languages roughly 100 000 years. Let's pretend that a language is "intact", i.e. mutually intelligible, over at most 1000 years. Then let's say that independent of population growth during this time we've kept at a constant 5 000 communities, at least. That means half a million languages, and we're counting generously. That means that less than 2% ar alive today, and we want to study the extent of our capabilities as humans on this. It is not futile and this count is not very accurate (by far). However, just. Keep this in mind will ya?

This is a rather trivial and obvious observation, but I think that this text is not meant to be read as what linguists should do, it's rather an answer to that question "why should we care" asked by someone as un-empahtic as to not understand that people identity with their language and to not care that it is taken away from them is just wrong and enforcing colonial ideas that certain languages are better than others. This to me is a reminder that we still need to tell language communities and members of the privileged communities asking such questions as the one McWorther receive that:

Btw, y'all should give the UNESCO's Universal declaration of Linguistic Rights a read.

I'll do a brief sum-up here and then present my own thoughts. The text is 911 words and I doubt that McWhorter has exhausted all his reflections on this topic, let's just keep that in mind. In this text he answers a frequently asked question "if indigenous people want to give up their ancestral language to join the modern world, why should we consider it a tragedy?". This is a common question face by linguists, and a very important one that should be addressed with great care and respect.

He dismisses the earlier linguistic-relativist argument he used to put forward, i.e. that each language represent a different world view and therefore another way for us as a collective human society of viewing the world.

Now, he rather puts forward two other arguments:

1) languages are important markers of community and identity, when people lose their languages they lose their culture and history.

2) He writes languages are scientifically interesting even if they don’t index cultural traits. They offer variety equivalent to the diversity of the world’s fauna and flora.

In other words, even if the linguistic relativism part of linguistic diversity isn't interesting, the basic question of linguistic typology is. I've made an attempt at formulating that question by myself, based offa Hjelmslev and Boas, I can't know if this is what McWhorther is interested in. Here we go:

Linguistic typology aims to map out the logical possible options of linguistic diversity and then see how actual languages are distributed across that design space, correlate that with genealogy, contact, known grammaticalization paths and the likes and then from the resulting knowledge about what is more probable and what is less probable possibly discern something interesting about human nature and cognitive capacity.

In order to understand ourselves as a species better we need to study what we can do, what diversity we are capable of.

McWhorther then finishes with:

These are the arguments I have ready for the “Why should we care?” fellow these days. We should foster efforts to keep as many languages spoken as possible, and to at least document what the rest of them are like. Cultures, to be sure, show how we are different. Languages, however, are variations on a worldwide, cross-cultural perception of this thing called life.

To me, there are two very important things missing here. Firstly, the agency of the communities. We cannot as linguists, and certainly not as non-members of the communities, make predictions about what they want. We can let them know that their language is

a) a language (at all), this is sometimes misunderstood

b) equal to other languages

c) interesting

Just like all other languages it deserves a dictionary, a grammar, pedagogical books, a place in the political system etc. That we can do, that we can say. The public often seems ignorant of the fact that all languages are equal.

Languages with more speakers or more written down literature are by now means more valuable or better. This is a fact I find that I need to explain often, once to a frenchman who claimed that french was the only language with which philosophy could be discussed. Sigh. Another time it was someone who thought that the reason that English was spoken by so many was because it had traits that were just more optimal for communication. In answer to that question I recommend looking at this map of "Countries the UK has not invaded" and then have a long hard think.

If explaining this and showing interest gives communities more power and confidence, great. But we cannot tell them that they should be doing this or that. It is not our right. In Swedish we would call this to remove someone's "myndighet". Their right and competence to govern themselves. Imma Trekkie, so I can't help but think of some of the moral dilemma episodes where humans get put in zoos to be studied by much more advances alien beings. We can't be guilting people for having to live in a world where their standard of life, and the standard of life for their families, will often increase significantly if they learn the majority language of their region.

I don't think this is what linguists do, nor what McWhorter is proposing, but I think it's worth keeping in mind. The fact that languages are dying are tied together with larger patterns of urbanisation, cultural colonialism etc. You might wanna read this study on correlations between linguistic diversity and ecnomonic growth. We can do what we can in stressing the fact that all languages are equal and that we, as well-educated people with authority, find them all interesting to study. By doing that perhaps we can instill confidence and/or have an effect on the political struggle of that community. It's sad and crass, but by discussing matters like this as privileged people our voices sometimes can make a greater difference compared to the voices of the actual communities than we perhaps wish they would.

As for the second argument, if that was true then we need just document and study all languages currently spoken and then we need not care whether they live or die. That is not an answer to the question "why should we care that they are dying?", it's answering the question "why should we care that they are dying before we can extract all new information from them?".

Add to this line of thought the fact that 7 000 languages is actually not enough if we want to answer the larger typological question outlined above. Let's just do a quick count. Humans have spoken languages roughly 100 000 years. Let's pretend that a language is "intact", i.e. mutually intelligible, over at most 1000 years. Then let's say that independent of population growth during this time we've kept at a constant 5 000 communities, at least. That means half a million languages, and we're counting generously. That means that less than 2% ar alive today, and we want to study the extent of our capabilities as humans on this. It is not futile and this count is not very accurate (by far). However, just. Keep this in mind will ya?

This is a rather trivial and obvious observation, but I think that this text is not meant to be read as what linguists should do, it's rather an answer to that question "why should we care" asked by someone as un-empahtic as to not understand that people identity with their language and to not care that it is taken away from them is just wrong and enforcing colonial ideas that certain languages are better than others. This to me is a reminder that we still need to tell language communities and members of the privileged communities asking such questions as the one McWorther receive that:

all languages are equal

and we apparently need to be saying this over, and over and over again. Perhaps exactly because humans associated culture and identity so much with languages, and we already seem capable of viewing certain cultures as better than others. This questions is also often asked by people who do not speak many languages and have found language learning hard, giving them a skewed comparison of languages. This questions is closely tied with the other very frequently asked question: which languages are most difficult? Well, all languages are learned by infants in roughly the same time, so they can't really be that different. However, not all languages are equally easy for an adult Germanic speaker to learn.

Perhaps it needs to be said, I think diversity is great and it's very sad that languages are dying. But, the picture is larger and we mustn't let ourselves as linguist fall into guilting people just because we want to answer privileged people who cannot understand the fact that all languages are equal.

Btw, y'all should give the UNESCO's Universal declaration of Linguistic Rights a read.

Comments

Post a Comment