Food for thought: "a language is a dialect with a missionary and a dictionary"

We were at a workshop again (forth one in four weeks). This time it was at the Max Planck Institute of Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the workshop is a part of the Language In Interaction Consortium and it's on language evolution and diversity (from their "work package 5").

One of the presentation was on multilingualism in Southern Senegal, along the Casamance river. It was Friederike Lüpke of SOAS who talked, the title was "The necessity of small differences. Multilingualism as a social strategy in a shared cultural space". She presented their project (that we've mentioned here before): Crossroads - Investigating the unexplored side of multilingualism.

In her talk she rephrased a famous quote that is often attributed to Max Weinreich':

Rephrased:

This rephrasing made me think of language classification, "good" and "bad" language, dialects etc. I made this rather long post for you but there was just so much important to say, I hope you enjoy it. Please don't hesitate to contact us if you have questions of comments.

The original quote is most often used in linguistics and related fields to illustrate the point that the distinction between different dialects and between different languages is often not as crystal clear. Very often the classification and division is not motivated by things linguists care about, such as mutual understanding or similarities in grammar and lexicon, but rather based on the division of communities into political bodies such as tribes, clans, states, nations etc. From a western perspective our notion of the "nation state" is particularly important (you can read more about this here).

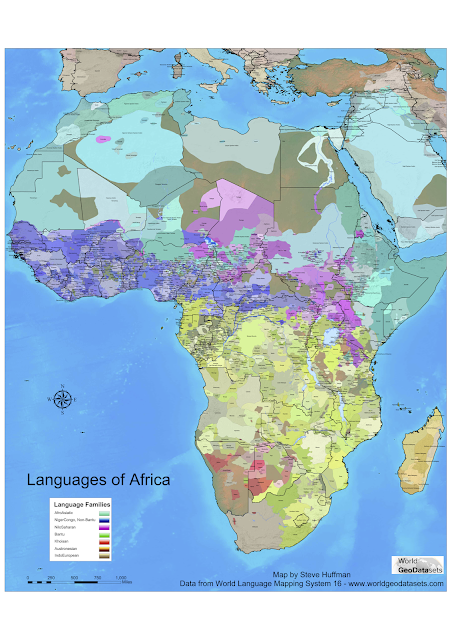

What the rephrasing of the quote highlights is the fact that in more modern times the division of varieties into languages and dialects is often dependent on the work of missionaries and others who make the first descriptions of a language. This is especially true in areas that have had very active Christian missions, such as Africa (see the Joshua project here for an overview). In the volume that Lüpke and Storch wrote on African languages, fieldwork and linguistic description in 2013 they also quote Blommaert (2008) who speak of dictionaries and grammars as "birth certificates" of languages.

Standards of languages

The Summer Institutes of Linguistics (SIL) is a faith-based, non-missionary organisation that is committed to serving language communities worldwide as they build capacity for sustainable language development. They collaborate with Bible translation organisations, in particular their sister organisation Wycliffe. You can read more about their history here.

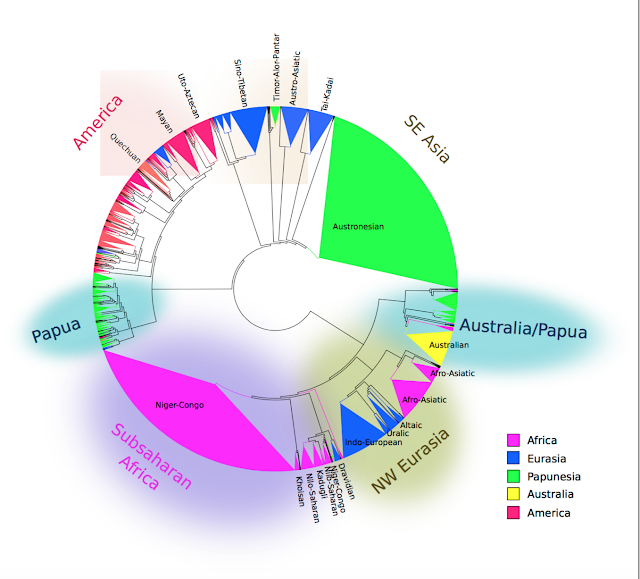

Their catalog of the world's languages, Ethnologue, is the most widely used standard for languages, their division and also their family relations. Also, is not only used by linguists. It is based on the work of descriptive linguists, many of them missionaries wanting to translate bibles and spread the word of God.

SIL is also the registration authority for the ISO-standard 639-3 the most widely used standard for language codes. ISO 639-6 is a code that aims to define three-letter identifiers for all known human languages. It is a set of codes for languages found in the ISO 639-2 standard for names (administrated by the US Library of Congress) and also additional languages from Ethnologue and other sources such as Linguist list. Together with the other code sets of the 639-family (1, 2, 4, 5 and 6, NB not all under SIL) it divides language varieties into languages and dialects and makes statements about their genealogical relations. The picture these standards creates is almost identical to the Ethnolgoue's classifications and family trees, most linguists don't actually use the other standards but just the Ethnologue.

It's great to have a standard to refer to, it facilitates linguistic research and commercial enterprises dealing with language (mainly translation services and multinational companies). However, we always need to have a critical stance and not just use any standard within reflecting on how it was created, by whom, for what and what consequences that information has for our current work. Is it necessary to use their standards for all kinds of linguistic research? Perhaps it very often is, but we should assume without first evaluating.

Science is hard, this is truth. You know, it's like Coldplay say in that song, funnily enough called "The Scientist":

I'm not saying that Ethnologue and the ISO standards are bad work and shouldn't be used, I'm just saying it's worth recognising the religious past and present of linguistics, the importance of early non-religiuos descriptivists and the quite poor state of description of all the worlds languages, and the consequences this has for classification and division of language varieties. Blommaert (2008), Lüpke and Storch (2013) elaborate on these issues in much greater detail than I have the space or competence to do here, please read their work if these matters interest you.

One of the presentation was on multilingualism in Southern Senegal, along the Casamance river. It was Friederike Lüpke of SOAS who talked, the title was "The necessity of small differences. Multilingualism as a social strategy in a shared cultural space". She presented their project (that we've mentioned here before): Crossroads - Investigating the unexplored side of multilingualism.

In her talk she rephrased a famous quote that is often attributed to Max Weinreich':

Original:

a language is a dialect with a navy and and army

a language is a dialect with a navy and and army

Rephrased:

a language is a dialect with a missionary and a dictionary

(see also Lüpke and Storch 2013, page 143 and Blommaert 2008, page 291)

(see also Lüpke and Storch 2013, page 143 and Blommaert 2008, page 291)

This rephrasing made me think of language classification, "good" and "bad" language, dialects etc. I made this rather long post for you but there was just so much important to say, I hope you enjoy it. Please don't hesitate to contact us if you have questions of comments.

The original quote is most often used in linguistics and related fields to illustrate the point that the distinction between different dialects and between different languages is often not as crystal clear. Very often the classification and division is not motivated by things linguists care about, such as mutual understanding or similarities in grammar and lexicon, but rather based on the division of communities into political bodies such as tribes, clans, states, nations etc. From a western perspective our notion of the "nation state" is particularly important (you can read more about this here).

What the rephrasing of the quote highlights is the fact that in more modern times the division of varieties into languages and dialects is often dependent on the work of missionaries and others who make the first descriptions of a language. This is especially true in areas that have had very active Christian missions, such as Africa (see the Joshua project here for an overview). In the volume that Lüpke and Storch wrote on African languages, fieldwork and linguistic description in 2013 they also quote Blommaert (2008) who speak of dictionaries and grammars as "birth certificates" of languages.

Standards of languages

The Summer Institutes of Linguistics (SIL) is a faith-based, non-missionary organisation that is committed to serving language communities worldwide as they build capacity for sustainable language development. They collaborate with Bible translation organisations, in particular their sister organisation Wycliffe. You can read more about their history here.

Their catalog of the world's languages, Ethnologue, is the most widely used standard for languages, their division and also their family relations. Also, is not only used by linguists. It is based on the work of descriptive linguists, many of them missionaries wanting to translate bibles and spread the word of God.

SIL is also the registration authority for the ISO-standard 639-3 the most widely used standard for language codes. ISO 639-6 is a code that aims to define three-letter identifiers for all known human languages. It is a set of codes for languages found in the ISO 639-2 standard for names (administrated by the US Library of Congress) and also additional languages from Ethnologue and other sources such as Linguist list. Together with the other code sets of the 639-family (1, 2, 4, 5 and 6, NB not all under SIL) it divides language varieties into languages and dialects and makes statements about their genealogical relations. The picture these standards creates is almost identical to the Ethnolgoue's classifications and family trees, most linguists don't actually use the other standards but just the Ethnologue.

Science is hard, this is truth. You know, it's like Coldplay say in that song, funnily enough called "The Scientist":

I'm not saying that Ethnologue and the ISO standards are bad work and shouldn't be used, I'm just saying it's worth recognising the religious past and present of linguistics, the importance of early non-religiuos descriptivists and the quite poor state of description of all the worlds languages, and the consequences this has for classification and division of language varieties. Blommaert (2008), Lüpke and Storch (2013) elaborate on these issues in much greater detail than I have the space or competence to do here, please read their work if these matters interest you.

Mutual intelligibility

I think Ethnologue does great work, and has good aims, as is evident from this comment from one of its editors:

The definition of language we use in the Ethnologue places a strong emphasis on the ability to intercommunicate as the test for splitting or joining (Lewis, editor of Ethnologue, in this article in the New York Times)

One can always ask here, what is really mutual intelligibility, can one human really ever understand another? I speak the same language as other Swedes, but I don't always feel.. fully understood if you know what I mean ^^. This is an existential question and linguists are rarely clear on what they exactly mean here, but for the sake of concreteness let's assume here we want to at least be able to communicate a classical story such as "world creation" or other culturally important events or objects between two healthy adults, such as the release of Beyonce's new album or the making of kumis. (We could also use collaborative tasks such as picking out objects etc.)

It is important to remember that Ethnologue cannot do mutual intelligibility experiments for all language varieties of the world, at best they can rely on reports on mutual intelligibility from field workers or speakers. See this post here for more discussion on mutual intelligibility.

In the case of SIL and Bible translations and the consequences that has for the division of language varieties into languages and dialects once can make the argument that if two communities cannot read the same Bible text and require two different ones they might be speaking two different languages. However, it is not clear how this decision process of Bible translations works and if the kind of language used in Bible translations and the quality of translations actually makes them a good comparative measure.

Another, and perhaps more practical, method is to measure the amount of shared words, i.e. overlapping lexicon. Ethnologue often seem to do this, you can find statements about the percentages of shared lexicon in language profiles, but it is unclear how often they use this measure and what material is actually being compared.

There is a database for this, the Automated Similarity Judgment Program, go check that out here. However, they use classifications from mainly Ethnologue, but also WALS and Glottolog and some additional ones of their making, to investigate the relationship between languages. You can see some stats of this here. They do not, as far as I know, make any claims to lump or join language varieties into different groups that they call languages based on shared lexicon. However, you can do that with the database and the first levels back of historical comparison so to speak kinda does this in a sense.

It should also be said that overlapping lexicon is not a perfect measurement either, but at least it might be consistent and more objective than many other methods.

Languages being overlapping dialects, sociolects, group language, slang, registers etc.

A "dialect" in English is a word used for sub-varieties of a "language", in particular those that have a certain geographic distribution (everyone from Omaha or Calcutta for exampel). There's also terms like "sociolect", sub-varieties of language based on socioeconomic status, i.e. class, and ethnolect, a variety of a language associated with a certain ethnic or cultural subgroup. The term idiolect is also used, an individuals language. There's tons of other relevant groups that use language differently from other groups: your family, academia, everyone that graduated from your high school that year, people who like Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure etc. We speak differently in different contexts and also differently over time. Sometimes we want to form a group or facilitate more efficient communication (professional jargon for example), other times we want to distance ourselves or mage even intentionally be ambiguous. All of this creates a very complex world where practically everything is variable to some degree, and yet there are rules for what to say when to achieve a certain function and not everything varies to the same degree everywhere and everywhen.

"Good" and "bad" language

Languages are often thought of as having one "true" and "correct" version - a central, "prototypical" version. This is most often the variety spoken at the power center, and most often a conservative version of that variety. We find this type arguing when people speak of "good" and "bad" language etc. Truth is, all sub-varieties of a language are equally members of that language. That being said, some varieties are more widely understood or will be more often used in formal contexts, higher education etc. It is the ministries of education in all countries duty to try and give all children an equal chance in life, this also includes giving them access to a language that will mean less discrimination, access to more context etc.

Such an education does not have to to involve shaming of other varieties though, pointing out that there are different varieties and teach when to use which is not the same as talking of "bad" and "good" language. There is a point to arguing that there is no such thing as "one correct language variety", but it is also true that children come to school with different backgrounds and to ignore that there is a variety that will make them more probable succeed in their future life is to give those that do not have access to that version and those circles of society a disadvantage.

Btw, using the standard in certain settings might often be highly inappropriate, such as when visiting relatives in areas with a radically different dialect from the capital. That might result in creating an unnecessary distance that might be taken as rude. Similarly, speaking certain dialects in formal contexts might make people more trusting and positive. Honestly, why do you think George Bush junior spoke the way he did.. ?

Illustrating messiness

I made this picture for a presentation, its messiness is intentional. It's showing several different layers at once, "languages", dialects, sociolects, other groups and the individual (the image makes it seem as as if they are being consistent across the categories, this is a lie). In the left corner we have a the British empire as the representative of the empires and nations and other large political bodies, in the right corner we have a linguist (actually me, because I didn't want to embarrass/shame anyone else).

In this messy world of ours we all make assumptions about what to lump and join, which features to use and which to discard. A linguists division might not always be ideal either, hopefully at least it's good enough for the needs of that linguists right then and there. In order to talk to each other linguists, and all other researchers for that matter, use standards such as the Ethnologue. Do not let this fool you into thinking the world is that simple though. (And we haven't even started talking about contact languages and sign languages yet ^^.)

There is also the relevant notions of doculect (a language variety as described in a specific source), languoid (supersets of dodulects) and glossonym (name of languoids). I would talk more about this here, but there's an already great post here and I have little more to add. The term endonym or autoym is also used to refer to the terms and groups that the speakers themselves make for their language and community.

Okay, that's all for now. Thanks for reading, be sure to talk to us if there's something you want to ask, would like us to elaborate on or just tell us. All comments, friendly hellos and fiery criticism is appreciated.

References:

Blommaert, J. (2008) Artefactual ideologies and the textual production of African languages. Language and Communication, 28 (4), pp. 291–307

Lüpke, F. & Storch, A. (2013). Repertoires and Choices in African Languages. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. Retrieved 31 Oct. 2014, from http://www.degruyter.com/view/product/184444

Very interesting topic Hedwig. This is something I have had to grapple with since I extended my research to include Eastern Arnhem Land languages. In Eastern Arnhem Land, people have ignored the efforts of missionaries and colonists to organise the language names and continue to use their own labels, which are very confusing to the linguist! There are two main levels to the taxonomy. The higher level uses the word for 'this' in each variety to name it. This means we have informative recordings of people saying 'I speak this language' which is rather ambiguous as to whether they mean 'this' or the dialect name. And mostly people prefer to use their clan name to name their language, which isn't always so useful for the linguist as these names clan-lects may vary greatly from one another or very little. And of course people may use a variety which is not the same as their clan-lect most of the time. As well as Friederike's work I found Christian Doehler's ICLDC 2013 paper quite useful for thinking about ideologies of language naming and language boundaries: http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/26087

ReplyDeleteThank you Ruth ^^! I basically just wrote this post based on experiences from my studies at Stockholm University and also based on lectures I've held to high school students on linguistic typology. I was thinking of making it even more extensive, but I had to draw the line somewhere.

DeleteI really like your comment, it shows exactly the kind of "messiness" that is so common and natural, and that we need to be able to deal with in a better way.

Also another reference that I found very useful, from one of your future ANU colleagues: Rumsey, Alan. Lingual and Cultural Wholes and Fields. Experiments in Holism: Theory and Practice in Contemporary Anthropology. 127–149. (6 November, 2014). Email me if you'd like a copy

ReplyDelete